“Life can even bring down the strong”

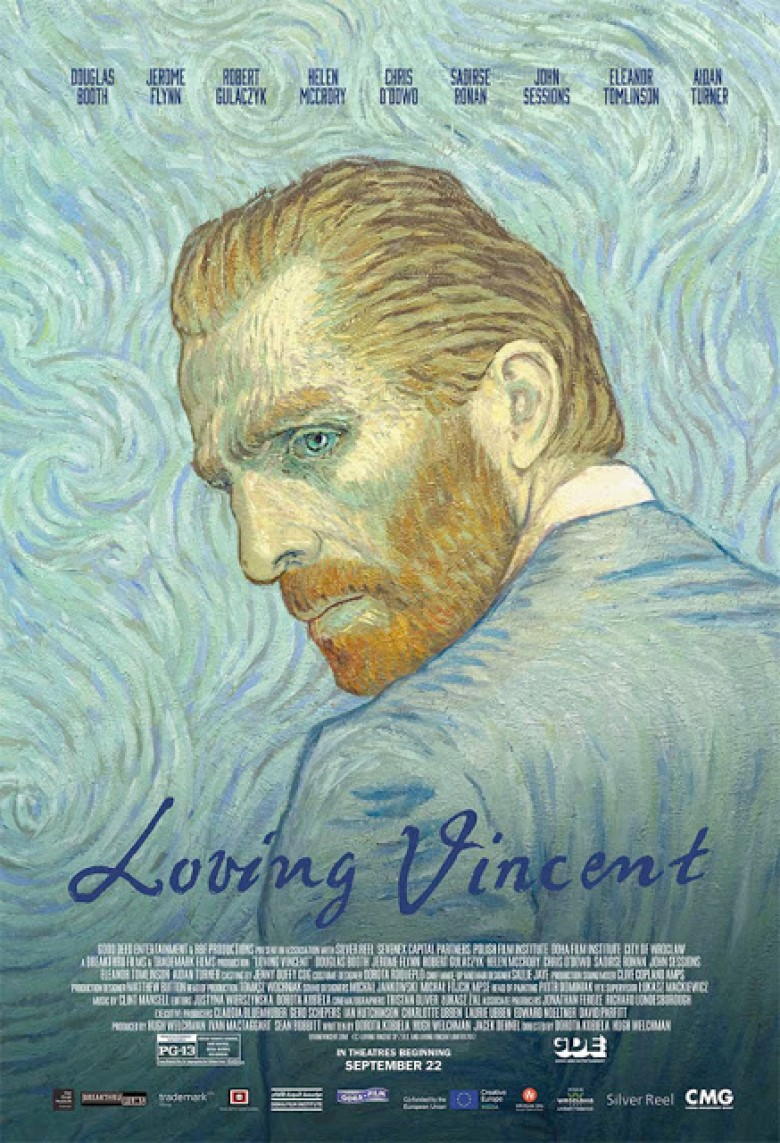

The stats are incredible: 125 artists animating a feature-length film over seven years based on 800 personal letters with 65,000 individually-painted oil frames. You read those numbers and wonder if it was worth the trouble when a traditionally shot narrative featuring its faux “rotoscoped” actors would have been enough. But there’s something about the insanity of directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman‘s vision that mirrors the ambitiously chaotic style of a genius such as Vincent van Gogh. You couldn’t represent this enigmatic character without having at least a little expressionist flair. And since we don’t know what truly happened in the days after his suicide, why not craft your hypothesis around the subjects of his work left behind? Suddenly Loving Vincent becomes like a letter from the grave.

It centers on Armand (Douglas Booth), the son of van Gogh’s close friend Postmaster Joseph Roulin (Chris O’Dowd). Vincent (Robert Gulaczyk) sent a letter to his brother Theo (Cezary Lukaszewicz) that sadly got lost in transit. Now, even though the latter was at the former’s bedside before he passed (from a self-inflicted gunshot wound two days earlier), that letter remains unread. The idea it might shed light on his suicide has Joseph intent on seeing it delivered. So he entrusts Armand with the task, much to the boy’s chagrin. His search for Theo ultimately leads him on journey to Auvers-sur-Oise, the place where van Gogh took his life. There he meets many of Vincent’s acquaintances, listening to their disparate recollections. Armand can’t help questioning everything he had known.

This artist that he never understood despite his father’s affection becomes more than just the caricature he knew through second-hand stories and drunken run-ins. He meets those who would call Vincent a friend (Aidan Turner‘s Boatman, Eleanor Tomlinson‘s innkeeper’s daughter Adeline Ravoux, and John Sessions‘ purveyor of paints Pere Tanguy) and others who despised his very existence (Helen McCrory‘s Louise Chevalier, the local doctor’s housekeeper). Armand hopes to speak with said doctor too (Jerome Flynn‘s Gachet) as all accounts point to him as being there at the end. Is he a suspect, a grieving mourner, or an opportunist? Was his daughter Marguerite (Saoirse Ronan) Vincent’s lover, friend, or a virtual stranger? Could van Gogh have pulled the trigger at this specific time or was it perhaps foul play?

These are the questions Armand asks as the simple duty of delivering a letter becomes embroiled in a mystery beyond anything the police ever cared to pursue. van Gogh himself admitted that the wound in his stomach was the result of a suicide attempt so there wasn’t any reason to look for an alternative cause. There probably still isn’t now besides the fact that Armand’s curiosity has simply gotten the best of him. He’s let village gossip consume his mind, forgetting everything else whenever a new “clue” arises. A drinker himself, some trouble is caused and accusations do fly. And for their part some of those caught in his crosshairs do feel guilty for reasons still unknown. Vincent was a complicated man and his death proves the same.

But this isn’t some “true crime” tale angling for podcast syndication. Suicide remains the consensus and Loving Vincent doesn’t reveal new evidence. It instead becomes more about young Armand finding himself later than most much like Vincent did. van Gogh started painting at age 28 and yet was prolific in his output over the next nine years before his passing. So Kobiela and Welchman use his demise as the impetus for Armand escaping the monotony of his own wasted life for a path towards his future career all while utilizing around 120 of the artist’s actual paintings for visual inspiration. They modeled their characters off of those canvases whether real people (the Roulins and the Gachets) or those created for the story (the Boatman and others).

You could say they’ve made their film through van Gogh’s eyes despite his already being gone. We’re experiencing people that he knew as well as the locations he revered enough to immortalize on canvas through the lens of that work. We also learn some of the harder details like depression, financial woes, isolation, and mental institution stints—each one a fact rather than excuse for what ultimately occurs. And all the stories from those we meet arrive via flashbacks in black and white, the crisp realism of these scenes perhaps more astonishing than the heavy paint and colorful swirls of the present. The film takes from Citizen Kane in this way with its “untold” behind the scenes tales full of candor as recalled by those who lived them.

The whole is therefore a fitting tribute to van Gogh’s life and those who called him friend during it and after. It really is a sight to see paintings like Portrait of Dr. Gachet, Marguerite Gachet at the Piano, La Mousmé, and Starry Night Over the Rhone come to life too. My favorite moments are when wide-angle shots lose the clarity close-ups possess so that faces become flat color fields within these expansive environments of thick brushstrokes and forever-moving phenomena. It’s like the air itself surges around each character, the surrealism of surfaces in stark contrast with the real world movements performed. That skewed filter of reflecting light transports us onto a plane of vision only attained when looking at this master’s work. That’s now where he remains.

Some may take issue with the story’s overly convoluted mission to uncover a hypothetical truth no matter who has to be taken down to get it, but the film makes up for what it lacks in narrative ingenuity with unparalleled aesthetic recreation. With that said, however, I did enjoy Armand’s “case” regardless. I enjoyed discovering details about those Vincent knew and loved in his own secretive way. To see that overwhelming shyness juxtaposed with the fiery temper that had him storming off and cutting ear from head is to go deeper into the inner-workings of a man tortured by the gift of volatile inspiration. And if we learn nothing else it’s that van Gogh painted without pause. It’s that same dedication upon which this beautiful memorial was built.

Score: 7/10

Rating: PG-13 | Runtime: 94 minutes | Release Date: October 13th, 2017 (UK)

Studio: Altitude Film Distribution / Good Deed Entertainment

Director(s): Dorota Kobiela & Hugh Welchman

Writer(s): Dorota Kobiela, Hugh Welchman & Jacek Dehnel