“I’ll bet heavy on the favorite”

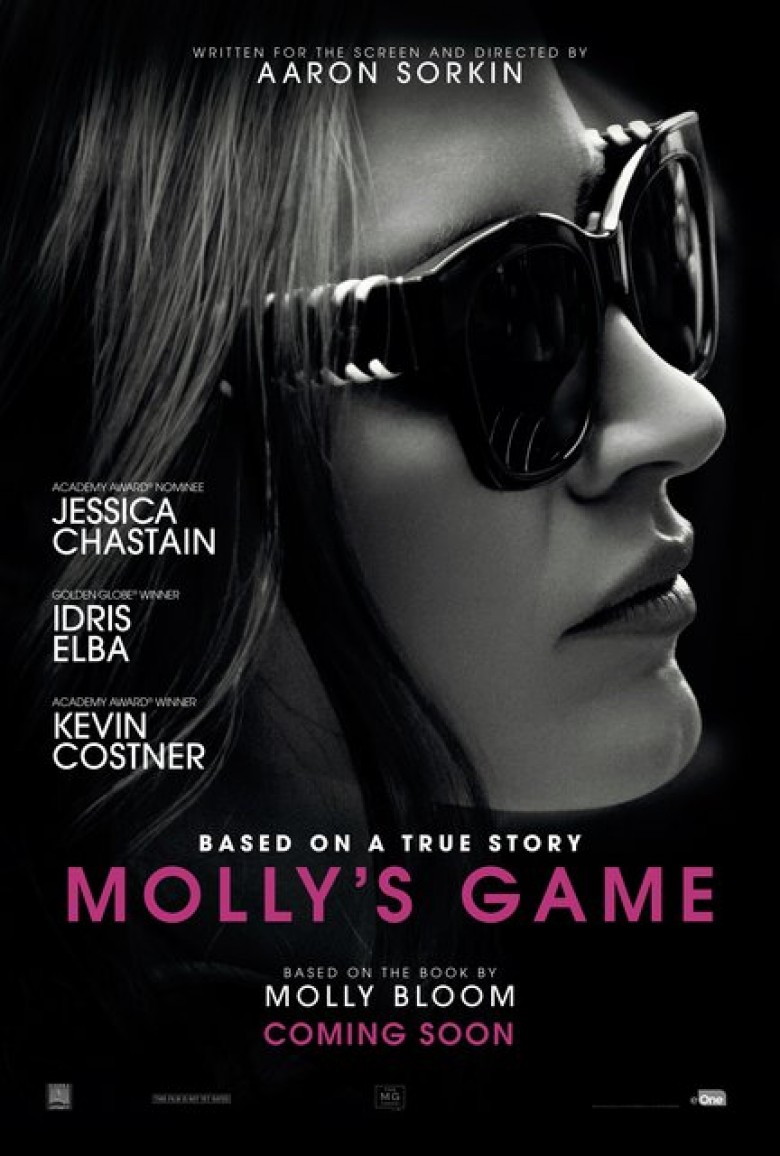

There’s a common theme throughout much of Aaron Sorkin‘s work the past few years of focusing on the unlikely redeemable qualities of figures easily reduced and reviled by a general public quick to judge without all the facts. You see it in The Social Network and its quest to humanize the abrasive wunderkind at the back of Facebook. It’s there in “The Newsroom” and its desire to show what a media network with integrity in the face of ratings wars can look like. And Steve Jobs may epitomize it most by giving this obviously difficult-to-work-with and hardly sympathetic icon a literal redemption arc. So it’s no surprise that he’d gravitate towards Molly Bloom‘s memoirs and her sincerity about wrongs committed and everything she did correctly before and after them.

Bloom is an almost-Olympian, a promising would-be law student turned madam of an “illegal” poker operation that ran for years in both Los Angeles and New York. She went from burned-out professional athlete in desperate need of a break before pursuing college who’s crashing on her friend’s couch while working as a cocktail waitress to respected woman with the power to possess the type of dirt that could ruin famous lives and not need to use it. She’s on par with the Zuckerbergs and Jobses of the world, where creating enterprises from the ground up that work on a multi-million dollar spreadsheet is concerned. But while they’re remembered for stabbing friends in the back and building empires atop them, she relented. Like a nicer Will McAvoy, she’s principled first.

And while Sorkin’s script for Molly’s Game dives too hard at the very end to place an asterisk on that integrity as though it was instilled in her by a misunderstood father (Kevin Costner) whose tough love was derived from self-loathing and shame, it also acknowledges that he was but a footnote whether important as a motivator (to fear or hate) or not. There’s a reason that Larry Bloom disappears for the majority of the film and it’s the fact that Molly (Jessica Chastain) didn’t need him. She didn’t need anyone. She saw an opportunity to be successful—to win—and she took it. She knew her worth above the strong-arm tactics of the men who believed they led her through success’ door. Molly Bloom was wholly self-made.

Perhaps that isolation led to inevitable mistakes with drugs, lax background checks, and tendencies to stake players beyond their means. Or maybe those aspects are simply caveats to a just left of squeaky-clean life she still attempted to lead despite it all. Either way, the fall from those initial heights was cemented once she went full-tilt and made things personal. What was to be a short stint of excitement and networking before going back to her original law school plans ballooned into a mission to prove to herself (and those who wronged her) her exact capabilities. The fun gradually devolved as she recognized the cost of this career. Eventually her clientele became heavier than deep-pocketed celebrities. Eventually armed FBI agents were knocking on her door with handcuffs ready.

Sorkin (and perhaps Bloom, I haven’t read her book) has his own fun with a fast-paced back and forth construction moving between past and present for optimal impact. The start is a cheekily delivered “screw you” to all those armchair quarterbacks prone to judging and assuming without knowing one iota of the guts, skill, and pressure the subject at-hand demands. This is followed by the arrest we all know is coming—one that strangely arrives a whole two years after Molly stopped her poker games and conveniently right after the publishing of her book describing everything that went into them. So we know where she came from and the predicament she finds herself in. The rest unravels to share the details leading to that predicament’s severity.

But it’s more than that too. Molly’s Game isn’t about her fate or even poker. A film doesn’t have to be about the subject’s actions when she herself possesses the dramatic gravitas to hold our interest regardless. This is why it really doesn’t matter whom these high-profile people are that she refuses to name. Who cares if “Player X” (as played by Michael Cera) is actually Tobey Maguire or some other A-list actor with the purported sociopathic hubris to admit he revels in destroying lives? All we need to be aware of is that “Player X” has power and is willing to use it. All we need to know is that Molly refused to buckle and let him defeat her. He isn’t important. He’s a stepping-stone.

They all are. Every single character from the players she liked (Bill Camp‘s Harlan), those that annoyed her (Chris O’Dowd‘s Douglas), those that cheated her (Joe Keery‘s Cole), and those eccentrics she should have known were more than meets the eye (Jon Bass‘ Shelly) is a pawn in her game. Their inclusion is a result of her invitation and their ability to help or harm her a consequence of her ascension. Sometimes they provide comic relief and other times extreme violence, but their actions are never more important than her reactions. She had the means to destroy so many of them, but that wasn’t her intent unlike “Player X.” Instead Molly sought to be compassionate. She looked to provide an escape and when necessary another from the first.

These recollections and anecdotes are thus for our benefit. They are a defense to win us to her side and agree that she couldn’t have known just how bad some of the players at her table were. She’s more or less pitching the same tale to her lawyer Charlie Jaffey (Idris Elba), to have him believe that she’s an inspiring success story drowning under the weight of details outside of her control yet also unwittingly facilitated by her. Molly Bloom is defending everything she is throughout this wild story so as not to let her mistakes define her life. She’s striving to let her ownership of those mistakes and the strength and courage that entails (despite numerous opportunities for salvation at the expense of others) define her instead.

And for the most part it works. These are her memoirs so they shine her in a sympathetic light being from her perspective. If she has evidence on all those clients, there’s no reason for her to lie. It therefore becomes utterly fascinating to learn the ebbs and flows, watch as the legal process ruthlessly ties her hands, and witness addiction consume so many. Chastain is fantastic in the role, her thick skin of sarcasm and deflection just hiding the fear of the unknown she faces when the realization of what’s unfolding is afforded full transparency. I could have done without the shoehorned therapy session with Dad at the end (especially since her decision was already made), but one unnecessary scene within two-plus hours is a commendable ratio.

Score: 7/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 140 minutes | Release Date: December 25th, 2017 (USA)

Studio: STX Entertainment

Director(s): Aaron Sorkin

Writer(s): Aaron Sorkin / Molly Bloom (book)