“In the sun we find our purpose”

It doesn’t get better than The Village where M. Night Shyamalan is concerned. That film was a perfect confluence of his screenwriting and directing capabilities, a tale of love and protection through drastic measures as metaphor for the struggles of parenthood steeped in heavy emotion and guilt without regret. A marketing campaign billing it “horror” ruined any chance for success with audiences unwilling to look past the auteur’s penchant for twists. Its target demographic is perhaps still unaware of how much they’d enjoy its nuance and hope if ever to give it a chance. Shyamalan created a world from within ours, a sanctuary as beautifully conceived as it was rife with danger. He did the same with Unbreakable and the vastly underrated children’s parable Lady in the Water.

This was the Shyamalan that won me over to endure any missteps (The Happening) with the promise for additional greatness. This period most labeled as his downfall after moving away from the shocking tricks that built his name showed exactly what he had in him to create. And I too started to think he might never reach those highs again after mainstream franchise possibilities disappeared (The Last Airbender), star-vehicles flopped (After Earth), and low-budget successes (The Visit) fell into surface appeal devoid of the depth of character he once mastered. So his latest Split brought with it cautious optimism. Would it use its premise to dig deeper into the human psyche and unlock yet another new world? Or once again prove mere gimmick exploited for scares and laughter?

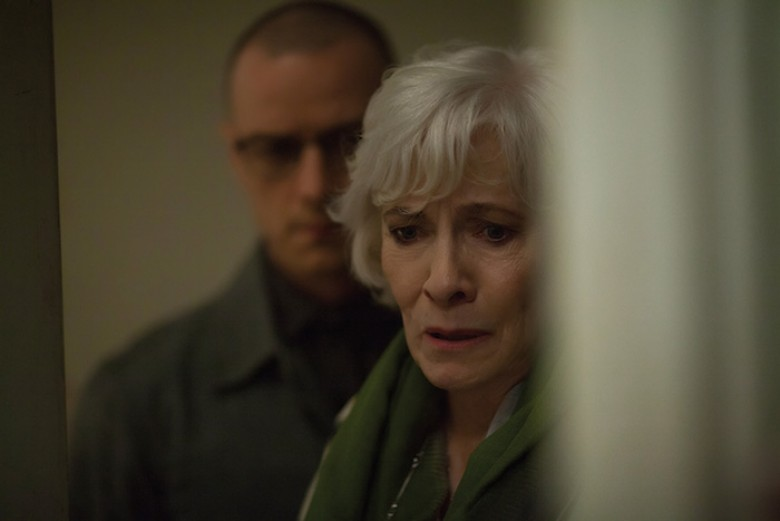

The answer lies with the former as Split reveals itself to be a magnificent return to form—a high-concept thriller utilizing dissociative identity disorder, trauma, and contemporary political turmoil to create a richly intuitive glimpse at our capacity for self-empowerment. It’s about a man named Kevin (James McAvoy) fractured into twenty-three diverse identities shielding him from the horrors of his past, but even more about a teen named Casey (Anya Taylor-Joy) who shares more in common with her captor than she could ever imagine. Shyamalan crafts a sort of anti-Village with a world full of the tragedies Edward Walker and the rest strived to avoid. But it’s also very much the same: a world believing itself to be safe despite reality showing that idyllic fantasy as a lie.

Evil has always existed; some have simply been able to avoid it longer than others thanks to wealth, race, gender, and/or countless other factors. It exists close to home, often inside those you love who may or may not understand how to stop it or even that it’s taken control. We see a change of attitude, demeanor, and identity in Kevin because it’s a by-product of his split personalities (a result of trauma at the hands of evil). Alongside the aspiring fashion designer “Barry” with high ambitions and hard-fought stability—the self who controls the “light” so Kevin can integrate with society—is the sternly fastidious “Dennis” guarding Kevin from the world’s always lurking evil. But we also see it with Casey—her childhood innocence a distant memory.

To she her change is to witness flashbacks as a young girl (Izzie Coffey) hunting with dad (Robert Michael Kelly) and uncle (Brad William Henke). We’re sent to the moment when everything changed, when evil was unleashed upon her. Whereas Kevin broke apart into victim and savior, Casey steels herself into becoming both. They each retreated from society to be alone, detaching themselves to deal with the struggles others couldn’t even imagine. When we meet them, however, something has happened to Kevin. Something has triggered his fear to bring forth “Dennis” and “Miss Patricia”—together dubbed “The Hoard” by his other personalities—to protect him. Their plan is to unleash “The Beast”, a part of Kevin that’s ready to open the world’s eyes to the nightmare surrounding them.

It’s a powerful sentiment that Shyamalan handles with care to not stigmatize DID, but let its exceptional properties rise to the surface. Thanks to a wonderful performance by McAvoy as each piece of Kevin’s mind, the disease isn’t rendered evil as many feared after watching the trailer knowing Hollywood’s history of sensationalizing mental illness. Special pains are taken so the audience knows evil attacked Kevin, his psychological response creating these versions of himself to fight back. Everything he does—everything “Dennis” and “Patricia” hope to accomplish through “The Beast”—is to seek justice. The world sees a villain consuming those lucky enough to never know suffering. “The Beast” sees himself as a hero returning the Earth to those worthy and willing to not take it for granted.

“The Beast” has been created to help victims like Casey find the strength to escape their predators. He’s evolved from pain, enlightened to the reality that things aren’t what they seem. He’s a result of Kevin’s doctor’s (Betty Buckley‘s Dr. Fletcher) support, a manifestation of how extraordinary mankind can be when backed into a corner with nowhere else to go but through its pursuer with a righteous fury. For “The Beast,” “Dennis,” and “Patricia,” that pursuer is a public unable to fathom what trauma is capable of creating. It’s a society that laughs and dismisses people as insane rather than victims coping with tragedy. He must become that which they fear to show them it isn’t an act. He will become evil so the “innocents” know his pain.

It’s a chilling progression without twists. Everything’s built through plotting whether the carefully exposed pasts of Kevin and Casey or keenly measured actions of Dr. Fletcher’s optimism and the out-of-touch happily-ever-after delusions of “Dennis'” two other captives, Claire (Haley Lu Richardson) and Marcia (Jessica Sula). We watch Kevin’s selves wield their power to compensate for injustices done to them: “Hedwig’s” heartbreaking desire for love, “Dennis” and “Patricia’s” drive for respect, and “Barry’s” naïveté in believing he remains in control. We watch Casey use survival instincts she’s tragically been forced to cultivate, her truth hidden to escape the pity of strangers while also proving to be her hope for salvation. Split is about acceptance: finding the strength to come forward, remove the stigma, and know you’ve never been alone.

The idea that Casey and the other girls will escape becomes secondary to whether or not she and Kevin will reach their potential to take charge and no longer remain silent as dictated by the general populace’s notion that bad things can’t happen to them. Kevin is therefore a flawed antihero with McAvoy forcing us to sympathize with his plight even if we loathe his execution. And Casey rises to hero status albeit unwittingly. Her survival isn’t from Kevin, but the world at-large. He gives form to the warring factions of her own system of coping and allows her to acknowledge that she too can take control and show the world it can no longer blindly protect its monsters. The moment to expose mankind’s evil has arrived.

Score: 9/10

Rating: PG-13 | Runtime: 117 minutes | Release Date: January 20th, 2017 (USA)

Studio: Universal Pictures

Director(s): M. Night Shyamalan

Writer(s): M. Night Shyamalan