“It looks like they were trying to break out”

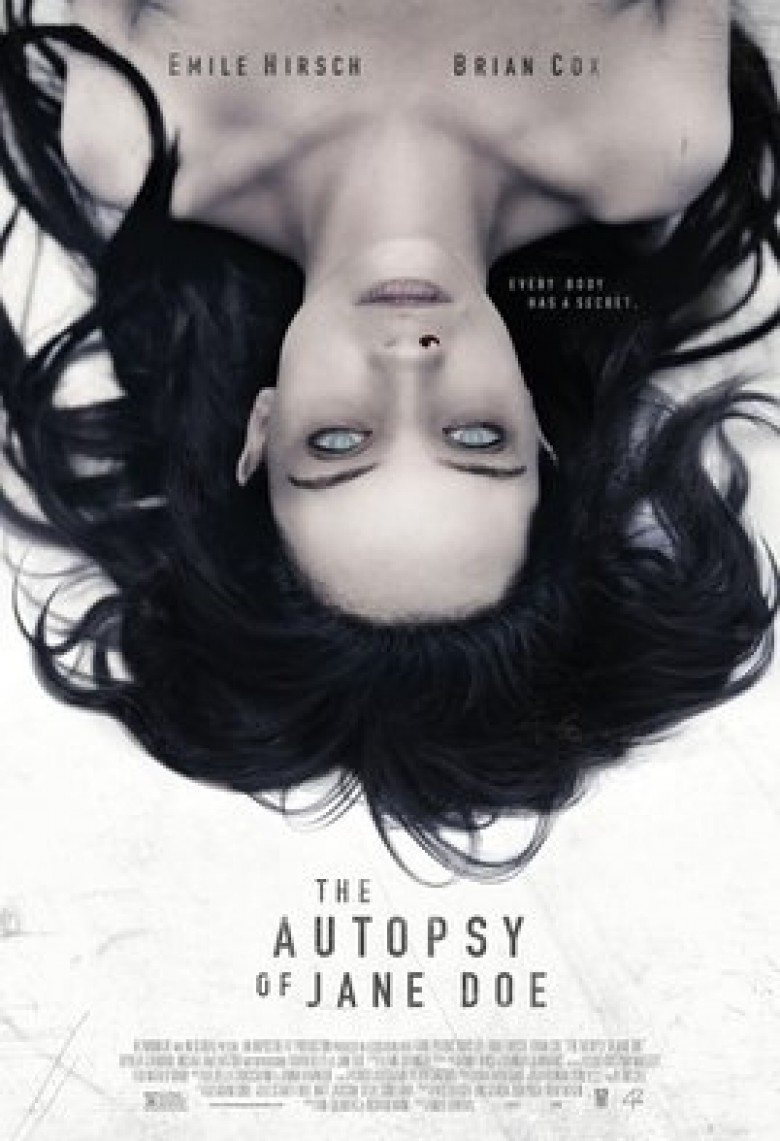

There’s no sign of forced entry. Two bodies are brutally murdered upstairs and a naked woman without a skin blemish is discovered half-buried in the basement. Sheriff Sheldon (Michael McElhatton) is at a loss. He can theorize the locals’ demise—even if it won’t quite fit perfectly—but he cannot spin the woman’s presence to the press. So unless he’s looking for a circus, her cause of death is paramount. Luckily, county coroner Tommy Tilden (Brian Cox) works late. And if he’s working so is son Austin (Emile Hirsch), his sense of duty after his mother’s passing keeping him by his father’s side despite girlfriend Emma’s (Ophelia Lovibond) hopes of breaking free. It should be like any other post mortem, yet we know it won’t be from the start.

This is The Autopsy of Jane Doe, written by Ian B. Goldberg and Richard Naing and helmed by Trollhunter director André Øvredal as his English-language debut. Its premise is simple, its locale simpler. For 80 minutes we watch as the Tildens perform their duties, each new discovery causing them to scratch their heads and hypothesize a reason. Tommy has spent his career with one rule: find the cause and leave the motivation to Sheldon. Austin sees things a little differently. He believes who the person was and what they do could help them in their report. But with every speculation he provides, Dad finds a practical explanation to refute it and find the truth. Every body that rolls in is just that, a body. That’s all he needs.

So what happens when science and logic aren’t enough? When Tommy realizes he cannot see everything with his eyes, something his wife’s death has already caused him to begin to understand? Austin’s gut instincts may have a poor track record when it comes to the cadavers they cut open, but could just be the only thing able to save them on this dark and stormy night. It’s just these two and their Jane Doe (Olwen Catherine Kelly), a diagnosis needed by morning. Three more bodies are held in cold storage and Emma has gone home. The lights flicker as their radio crackles. The video recorder blinks, capturing one revelation after another leading into strange, unexplainable occurrences. The impossible becomes possible as their chance of survival moves out of reach.

The minimalism with which the script advances is great because we’re allowed to dig into the mystery alongside the Tildens rather than find ourselves as voyeurs. We catalog their movements through a checklist, from external exam to internal, the first presenting Jane as seemingly pristine while the latter exposing trauma beyond the scope of a moral human’s imagination. More than one thing doesn’t add up, whether it’s time of death versus decomposition, or injury versus appearance. And as a creepy juxtaposition between a children’s song on the radio and the nightmare unraveling gets our minds racing to guess what might happen next, the answer begins to prove as straightforward as the narrative. The explanation tracks, but its presence in the story doesn’t. What exactly connects her to them?

As the stripped down plotting captures our attention, the lack of substance beneath these meticulous machinations causes us to relinquish all emotional attachment. We wait to see how the backstory of these men will play into the supernatural events occurring because there’s no need to tell us any of it if it’s not going to infer on the present. Those just happening to be the unlucky souls with scalpels in their hands when Jane is unearthed could work if we go into more depth with her past, but that’s not what happens either. Instead we’re treated to a random phenomenon wherein who the players are becomes inconsequential. The Tildens are nothing more than our potential victims, Jane their predator by proximity.

The result lends a clinical precision to The Autopsy of Jane Doe so that we can enjoy its construction and ideas if not truly revel in its execution. Tommy and Austin’s decisions are based less on authentic emotion than on the need to move the plot forward. The Tilden matriarch’s death looms to ensure that Austin skips his date. Emma’s intrigue at seeing dead bodies is introduced so that we know what the fridged cadavers look like. Jane’s escalating state of physical duress is merely a series of worsening expressions of suffering to fit a truth yet to be revealed. Goldberg and Naing have distilled the journey towards their endgame to its barest bones for purity of suspense, but in doing so they’ve made their characters objects rather than people.

So when crazy things happen and Tommy and Austin are pushed to the brink of sanity, violence, and sacrifice, nothing is surprising. Everything happens with a whimper because the screenwriters made sure each step fits perfectly with those before it. The only real fun to be had is in the autopsy itself because we never have a clue about what they’ll uncover next. Peat found under her fingernails? Shattered wrists and ankles? Internal stab wounds but no external entry points? Discovering each new level of injury had me leaning forward, but watching the Tildens acknowledge their precarious situation and need for escape never earned the same attention. I cared less about whether they’d make it out than I did the potential of Jane rising from the table.

It’s too bad, because on paper everything works. Øvredal has built an atmospheric set. Hirsch and Cox bring their A-games, even though they know this film isn’t out to win awards. And Kelly captivates in her stillness because the decision to use an actress rather than fake body forces you to wonder when she’ll move, rather than if. The problem is that the combination of their successes don’t add up to anything we can truly enjoy beyond its façade. All exposition—whether for the Tildens or the tragic subject of their autopsy—leads nowhere because it only infers upon their convergence (ten minutes in) and not what happens next (the other seventy minutes). So while the final product isn’t bad, it’s difficult not to instantly forget it.

Score: 6/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 86 minutes | Release Date: December 21st, 2016 (USA)

Studio: IFC Films / IFC Midnight

Director(s): André Øvredal

Writer(s): Ian B. Goldberg & Richard Naing