“I’m not the girl I used to be”

I like unreliable narrators because it’s fun to witness actions unfolding without knowing whether anything onscreen is real. The person could be a liar, schizophrenic, a secondary source ignorant to pertinent facts, or simply mistaken. So I got excited upon learning of Paula Hawkins‘ The Girl on the Train and its lead Rachel (Emily Blunt). Here was a character who literally knew nothing but what she was told. A raging alcoholic prone to nightly blackouts, her reality becomes the stories told in their aftermath. Her ex-husband Tom (Justin Theroux) filled in the blanks when they were together and now her roommate Cathy (Laura Prepon) can help once in a while, but mostly we’re left wondering as Rachel herself struggles to remember. Friday evening’s events are therefore anyone’s guess.

Where the story loses me is in its use of three unreliable narrators. Hawkins’ story isn’t about what we see (or don’t see) through Rachel’s eyes being given context by an absolute truth later. Instead it’s a puzzle spanning months of her, the object of her obsession (Haley Bennett‘s compulsive liar Megan), and the mother of her ex-husband’s child who lies to herself (Rebecca Ferguson‘s Anna). While this could be a boon to the mystery by confusing us with constantly diverting pathways, it just as easily provides too much information to inevitably ruin any surprises. Sadly the latter is exactly what The Girl on the Train does. By letting us into the lives of Megan and Anna—namely their extracurricular activities—process of elimination solves everything early.

The only thing worse than this is taking the time to explain in full detail what it is the filmmakers think we don’t yet know. In this case we do need some hand-holding because the truth is more convoluted than the red herrings splitting our attention, but that complexity doesn’t add anything to the result. It seems as though Hawkins—and her adaptors in screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson and director Tate Taylor—is so interested in creating a surplus of twists and turns that she forgets to ensure the main plot can effectively sustain them. The interesting character is Rachel and how she lets jealousy, addiction, and self-loathing affect her relationships with the others. What Megan and Anna do otherwise is inconsequential despite its prevalence and focus.

How abusive is Megan’s husband Scott (Luke Evans)? How smarmy is her psychiatrist Dr. Abdic (Édgar Ramírez)? How fearful for her baby’s safety is Anna? And how trusting in Rachel’s “harmlessness” is Tom despite all evidence pointing to the contrary? These are the questions bouncing around and yet the answer to all of them is quickly discerned to be: “It doesn’t matter.” A couple sex scenes and we’ve pretty much figured out the truth. We don’t know motivations or process, but we know the culprit and grow frustrated in the ruse. We grow angry that Detective Riley (Allison Janney) seems uninterested in doing any work unless her suspects come to her and bored of Rachel digging herself deeper into despair when the film pushes her to the background.

Blunt delivers an emotionally resonant, powerhouse performance we cannot ignore considering Taylor’s juxtaposition of her demeanor and appearance from a strung-out present and joyous past. She breathes life into Rachel as a broken soul desperate to shield herself from the truth as long as her hopes can be proven. Did she see Megan that Friday night she disappeared? Did she kill her in a fit of rage because of what Megan did that morning or because she was in the wrong place at the wrong time? It’s all there to captivate us and yet the film rewinds a few months to showcase Megan, the girl no longer visible. We learn about her infidelities, insecurities, and regrets. We learn about details that do little besides ensure Rachel is forgotten.

Each vignette may be short, but short is still too long when the person that matters is gone. We’re paying such close attention that we remember the man in the suit (Darren Goldstein) following Rachel. We remember what she drunkenly said into her phone about fantasizing a specific homicide scenario. We have words and visuals coinciding with distorted images in Rachel’s memory that hold the key to unlocking everything, but rather than sticking to them we watch Megan seduce her shrink and Anna’s paranoia. It’s all salacious distraction devoid of substance to titillate. It’s all there to remind us that The Girl on the Train isn’t an expertly taut mystery to be dissected or impressed by. No, this is a trashy romp seeking to entertain the masses.

And it succeeds in that goal: I was entertained. There’s such potential for more, though. Blunt knows this too because she renders Rachel into the sympathetic yet wholly untrustworthy mess needed for us to believe anything is possible. Her portrayal forces us to know in our hearts that she’s the murderer as strongly as we know she isn’t. To waste that power is a shame and I blame the writing. Either Hawkins’ source material can’t carry the weight of her complexity or Wilson’s translation made it so it no longer could. I lean towards the former because everyone outside of Rachel proves a two-dimensional stereotype filling a mold. While Blunt falls apart the rest clinically go through motions. They merely serve a purpose and never feel real.

This is the film’s greatest failure because we never care about Megan. Unlocking Rachel’s memory is the only reason to watch and it becomes an afterthought to filler padding runtime. The story is so desperate for us to sympathize with Megan and her struggles, but she comes across as a bored housewife automaton that never earns the tragedy of her past because we think she’s a psychopath and can’t therefore believe her tale. Her disappearance is only here to give Rachel closure she and we never anticipate is on the horizon. Rather than smart, this revelation proves random and weakly constructed. The payoff arrives out of nowhere to shock and the only one emotionally invested is Rachel as though everyone else was a cardboard figment of her imagination.

Score: 5/10

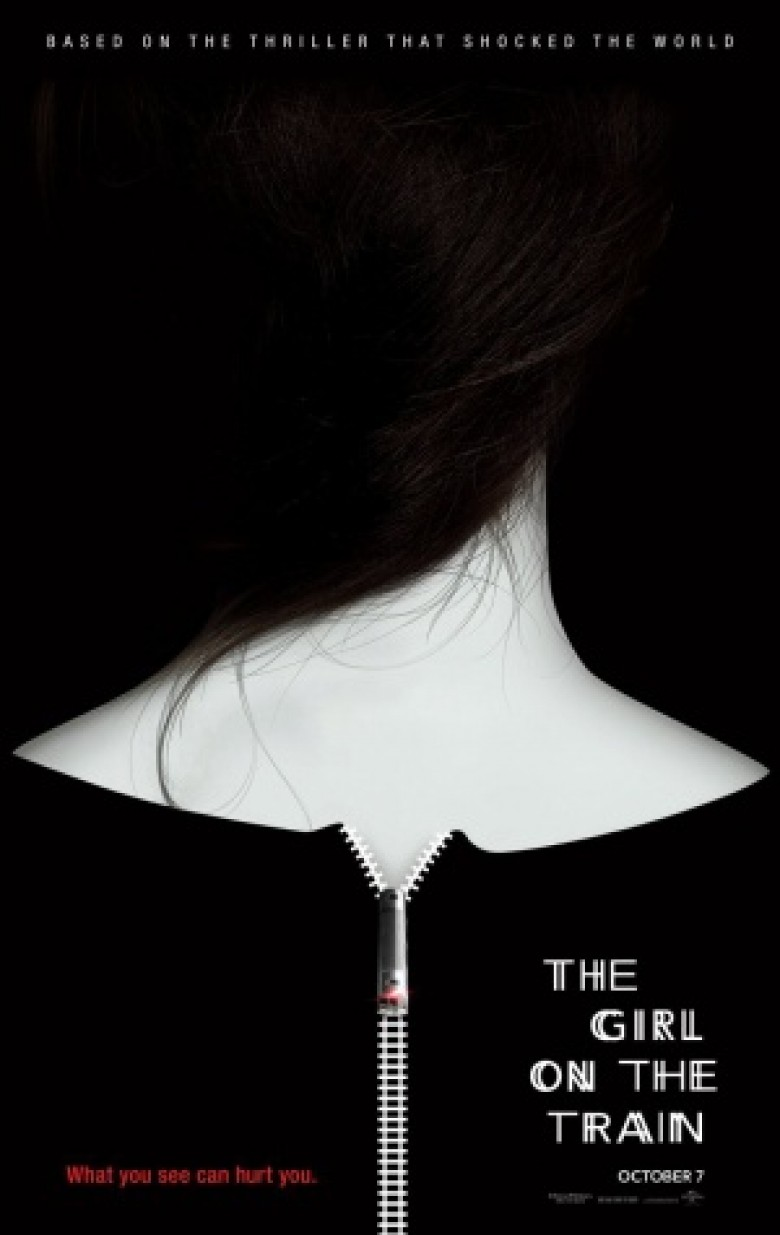

Rating: R | Runtime: 112 minutes | Release Date: October 7th, 2016 (USA)

Studio: Universal Pictures

Director(s): Tate Taylor

Writer(s): Erin Cressida Wilson / Paula Hawkins (novel)