“Aren’t you supposed to be home by eleven?”

The end credits of Clint Eastwood‘s Jersey Boys steal the show. A bombastic number lasting a couple minutes has the entire cast singing “December 1963 (Oh, What A Night)” with genuine excitement through a staged New Jersey street and it gives us exactly what the previous two plus hours couldn’t. Let’s be honest, “Jersey Boys” the stage musical isn’t that great when you take away The Four Seasons‘ songs and its brilliant use of a sparse set at the end of Act One. It’s a “Behind the Music” of four kids who broke free from the allure of mob life—mostly—to become rock and roll legends. The real appeal is in the theatricality. As soon as you attempt to make it a movie with locations, drama, and close-ups, the electricity that made it a Tony winner is lost.

It’s not a bad film per se. I was even going to give it the benefit of the doubt, understanding you don’t hire Eastwood to direct a jukebox musical if you aren’t going to ground it with realism. But then the end credit sequence began and I found myself smiling for the first time all night. The memories of hearing Bob Gaudio’s music emanating live from the stage while set pieces lowered from the ceiling and actors turned to explain the story came back. This was the musical that had so much buzz after debuting in 2005. This was the communal experience of watching as history unfolded before our eyes like we were in the audience at the “Ed Sullivan Show” or behind the glass at Bob Crewe’s studio. The theater made us participants, the film merely spectators.

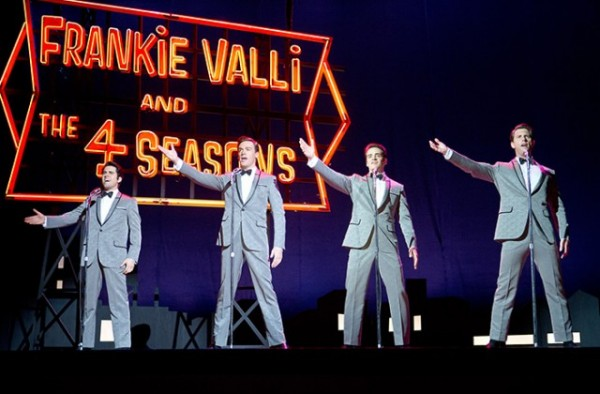

And that’s okay if you want a dry, no-nonsense biography of Frankie Valli (John Lloyd Young), best bud Tommy DeVito (Vincent Piazza), bass player Nick Massi (Michael Lomenda), and writer/singer/pianist Gaudio (Erich Bergen). Eastwood delivers this and then some, delving into the same events thanks to book writers Marshall Brickman and Rick Elice returning to script the film. We witness the emotions, the pent-up anger, the splintering of egos, and the unfathomable selflessness that still shone through despite all the bad times and missteps. But it doesn’t feel like a musical. It feels like Walk the Line or Ray—films about musicians that have concerts to serve the story and progress the plot. It may be identical on the page to the Broadway musical, but boy does it play completely different.

There are no crescendos to liven our mood, no stellar set direction thrusting us into the action by subverting our position to the stage. When the “Ed Sullivan Show” performance began I thought we’d finally see something cool—something to rival the ingenuity of the stage show—but Eastwood simply cuts to a flashback that commences a good thirty minutes of laborious diva moments killing all momentum it might have possessed. Only the authentic heartbreak of Young’s Valli, helpless as friends and family fall by the wayside, gives us something to grab onto. The climactic implosion is contrastingly depicted as a speed bump along his career’s evolution. We receive no opportunity to let drama sink in before the next check stop arrives. Tommy owes the mob a half million? A cut here, performance there, and boom, debt’s paid.

The film would have been better suited excising the fourth wall breaking too. Where it waves us in closer during the musical, it simply comes off as awkward onscreen. It’s never more out-of-place and abrupt than the first time Piazza’s Tommy speaks at us in the beginning, but it doesn’t ever feel right. There’s a disconnect in that we’re able to see the artifice whenever he, Lomenda, or Bergen turn our way despite the film desperately trying to hide those strings otherwise. As soon as we settle into the fact events are going to play out as they would during any other cinematic narrative, someone breaks character to give us exposition and we’ve lost our footing. It’s a continuous starting and stopping that I never could truly ignore, its inconsistent tone refusing to let me invest.

And that’s the greatest tragedy because Jersey Boys is impeccable elsewhere whether the aesthetic, music, or performances by a quartet of guys from television if any credits at all. The Jersey is pretty thick, but that’s part of the charm—one of the few over-the-top flourishes retained from its theatrical counterpart. Beyond that you do really get a feel for whom these kids are growing up as Tommy and Nick walk through a revolving door of juvenile delinquency, Frankie narrowly escapes it, and Bob lives the life of a saint in comparison. A good bit of humor is infused during this early period as each has fun with the others on their fantasy rise to the top of the charts. The second act unfortunately gets too serious—something the musical falls prey to as well if memory serves.

It becomes a tale of two halves with comedy excelling at the start and drama falling too heavily by the end. The tonal shift gives us something that would probably have been great in a bona fide dramatic retelling, but bookended by fun and games like it is here never provides the necessary time to properly transition. So we wait for the next song to pull us out and it arrives as just a song rather than the poignant metaphor for behind the scenes tragedy the screenwriters are hoping to achieve. In the end, all the problems I have are the same as those I had with the musical. Where the latter possessed spontaneity, excitement, and life to mask its shortcomings, the movie leaves them bare at the surface—a point that credits sequence proves tenfold.

Score: 5/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 134 minutes | Release Date: June 20th, 2014 (USA)

Studio: Warner Bros.

Director(s): Clint Eastwood

Writer(s): Marshall Brickman & Rick Elice / Marshall Brickman & Rick Elice (musical book)