Native Son at Paul Robeson Theatre is 90 powerful minutes of intense and compelling theater. At the center of this thought-provoking abstract play is a brilliant performance by Alphonso Walker, Jr. as Bigger Thomas, a 20-year-old black man raised in rat-infested poverty and soul-killing racism on the south side of Chicago in the 1930s.

Native Son is a journey into the mind and soul of Bigger. Playwright Nambi E. Kelley’s adaptation of the Richard Wright novel captures the essence of Bigger’s mind through the addition of a character who acts as the personification of his thoughts. Called "The Black Rat," excellently portrayed by Augustus Donaldson, Jr., he follows Bigger throughout the play, a shadow who sometimes tortures, sometimes cajoles, and sometimes tries to save Bigger from himself. But Bigger is ultimately at the mercy of forces beyond his control.

In the first scene, Bigger half-drags and half-carries an extremely drunk young white woman, Mary Dalton, to her bedroom. As she flirts with him, his fear and desire become palpable. After he maneuvers her onto her bed, her blind mother comes toward the room calling for her. Knowing if he is caught there, he will suffer grave consequences, he accidentally smothers her with a pillow. As the play unfolds, we learn that Bigger was recently hired as the chauffeur by this rich, liberal family. We follow his thoughts and actions, going back and forth in time, as this tragedy unfolds.

Central to the play is W. E. B. Du Bois’ concept of “double-consciousness,” which Director Paulette D. Harris quotes in her program notes. “It is a peculiar sensation…this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” Bigger’s struggle is that he is cannot seem to act from his own being, but instead always in reaction to how he is perceived by others. Throughout the play, Bigger and The Black Rat repeat versions of the line about looking in a mirror where, “…you only see what they tell you you is.” Bigger’s alcoholic girlfriend Bessie states, “They kill you before you die.” There is no way for these people to outrun the racism and poverty that define their lives.

Alphonso Walker, Jr. does not so much play Bigger as become him. There is not an inauthentic moment in his performance, nor does the audience ever perceive the actor behind the character. He expresses Bigger’s anger and terror, his lust and swagger, his desire to fly and be free, and his inability to experience his own being outside of how others perceive him in a masterly, riveting performance.

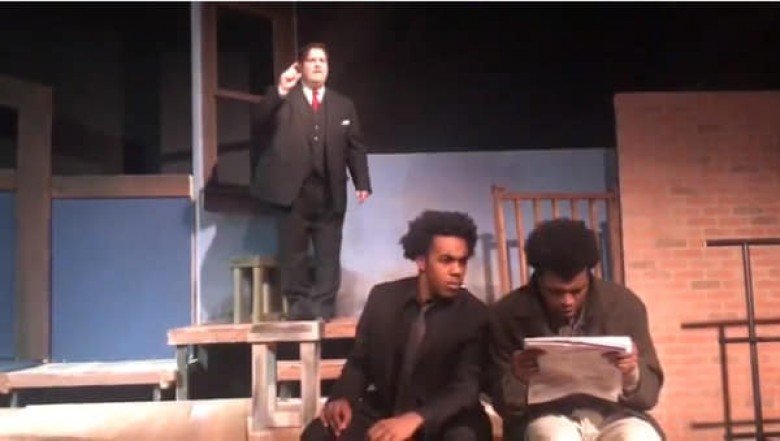

Augustus Donaldson, Jr. is completely in synch with Bigger as his shadow, The Black Rat. Wearing a black suit, shirt and tie, he speaks simultaneously with Bigger at times and follows him throughout the play.

Deborah A. Krygier is creepy good as the blind Mrs. Dalton, stroking her white kitty while spouting rich, white, liberal platitudes to Bigger that only add to his discomfort. Madeline E. Allard as Mary Dalton embodies the “rich girl looking for a thrill” stereotype, flirting with Bigger, drinking, and dating a communist in the person of Jan, well played by John Warzel. Janae’ Leonard is very good as Bessie, who smells of “gin and bleach,” expressing the frustrations and fears of a young black woman resigned to a life of cleaning houses for white people, and longing for better. Debbi Davis as Bigger’s long suffering mother, Jerai Kahdim as his younger brother, and Shawn Patrick Greene as a private detective round out the cast.

The stark set by Harlan Penn is a series of wooden platforms on multi-levels with a ramp on the upstage wall. Props and set pieces are minimal so nothing detracts from the unfolding drama. Sound, including gunfire, is by Elijah Cullen Tyner. The uncredited lighting works very well to highlight the terror Bigger feels.

Ms. Harris has assembled a cast worthy of this heart-wrenching play. In a very interesting and heartfelt talkback, the cast spoke of how they take care of themselves and each other during and after performances, the research they did to prepare for this play, and what feelings and realizations it has brought to the surface for them.

Native Son is a no-holds-barred play, and Ms. Harris and her cast do not pull any punches. The violence, language, terror and horror are all on vivid display. It is impossible to see Native Son and not be horrified and moved by the plight of the people who exist on the lowest rung of our society.

Native Son plays at The Paul Robeson Theatre through February 10th.