I'll charm the air to give a sound, While you perform your antic round~William Shakespeare

Macbeth, Act iv. Sc. 1

March 15th, 2000

Seattle, Washington

I live in an apartment that the landlord originally built for visitors to the 1962 World’s Fair. Flat roof, concrete deck, and a row of picture windows—motel-like. A place to visit, not a home. Outside, the dripping rain lures me into the kitchen to rout the wet chill with the hot steam of chicken soup.

Besides water, the only ingredient in my apartment to make soup is a package of tiny square egg noodles. I take the tight plastic package from the cupboard and hold it as I write a shopping list—onions, carrots, eggs, celery, chicken, and Asiago cheese. The tiny square egg noodles go back into the cupboard unused; this package of noodles is the touchstone.

My grandfather, who lived in South Buffalo his whole life, made chicken soup every week, sometimes twice a week. He modified traditional chicken soup with a bit of barley and a dash of tomato sauce. For my mother’s family, chicken soup was a staple. No one was allowed to eat the last of it. If one of my uncles reached into the refrigerator and found no soup, a report of blame and recrimination issued through the house, “Who ate all the G-damn soup.”

Every year, I spend at least a month in Buffalo. On the day I would leave Buffalo, my grandfather shopped and returned home with a package of tiny square egg noodles. “For your suitcase.” The way he said it made me think the package of tiny square egg noodles were magic beans. All I had to do was throw them in my suitcase and when I arrived in Seattle, I would have a pot of chicken soup. My grandfather died last May and this package is the last of my supply.

My grandfather’s sister Madeline mixed, kneaded, cut her own noodles. The fresh noodles softened her soup. One of their brothers, Salvator, was mentally ill and relied on Madeline to cook for him. One day while making noodles and boiling chicken, she told Salvator to stay for dinner. “Yes, Madeline,” he said and then he went to the basement. She heard a shot. Frightened she called the police. Papa, my other grandfather and a detective, heard the call and recognized his daughter-in-law’s maiden name. Papa was the first police officer on the scene. He found Salvator dead. When Papa returned to the kitchen, he said to Madeline, “Finish making your soup, there’s nothing else you can do.”

Home for me is where my family cooks and shares their meals. I was not raised in Buffalo, nor have I lived there the last fifteen years of my life. Regardless, Buffalo is home. On both sides of my divorced family, my grandparents’ dining room tables are family hubs. On my paternal side, Nana and Papa serve in courses. There are as many as nine if you count the sandwiches Papa pushes during card games. On my maternal side, my Gram holds court at the end of her dining room table: coffee, cigarettes, bacon and eggs in the morning; and ham sandwiches with sweet pickles on rye for her guest in the afternoon. On these dining room tables, my family eats roast beef, roasted potatoes, shells and ricotta, manicotti, Italian wedding soup, zucchini frittatas, barbequed spare ribs, NY steaks, pizza and Pepsi, chicken wings, and chicken soup.

I work in the restaurant business and in my family there are many good cooks, but I tend to be an inarticulate connoisseur. At my most peevish I say, “not so good,” or if it is good, I say, “Tastes just like Nana’s.” I’m not suggesting that every dish has to taste like my Nana’s to be good, but after eating I want to feel like I did as a kid—dazzled, full, loved, and sleepy.

But here is my snafu—when I cook, I’m a culinary knucklehead. I am over zealous with portions, especially pepper. I scald pans and my tongue. I char the onions, evaporate the soup, burn my cookies, or lose patience with what I’m cooking and eat it raw.

And according to both of my grandfathers—Grandpa and Papa—I don’t shop right either. Even though Papa is in Buffalo and Grandpa is dead, I hear them scold me as I shop: Grandpa says I should wait for chicken to go on sale, buy a few, and freeze the extra; and Papa complains I pay top dollar for everything. Even with my depression-raised grandfathers babbling in my brain, I go to one store and pay extra for the convenience. Just do something in your life against your family’s counsel and they’ll be shouting at you from miles away and from beyond the grave. If you miss them enough, you’ll rebel just to hear them shout.

I return from shopping with a puny fryer chicken. After cutting up the chicken and vegetables, I throw the torn chicken parts and the skinned onion and broken carrots and celery into the stockpot and let them float. The water foams and begins to boil. Papa calls the layer of burbling brown chicken grease scooma. “Never skim the scooma.” He says the flavors rise to the top.

Separating the boiled meat from the bone is high mess. I never wait for the chicken to cool. I do my own chicken dance as I flail my burning greasy fingers in the air. My hands scorched, I drop the shreds of boiled chicken back into the broth. Next morning, the soup has cooled and I hope congealed although it is never condensed enough to congeal. I skim the fat off the top and there is my soup—nothing more than colored water.

Then I start making phone calls and along comes the advice: My father says I turn the heat too high when I simmer, and I must learn to master the fine art of reduction; Nana says it isn’t my fault that chickens aren’t as flavorful as they once were, and so I should add bullion; my brother Scott wonders why I keep calling over such an elementary dish; and Gram says I should just come back home to Buffalo and eat her chicken soup.

Scott suggests roasting the chicken for flavor before boiling. When I quit smoking, I arrived at his apartment in Portland, Oregon in a frenzy of withdrawal, carrying a pouch of Chinese herbs. The herbs tasted like dirt. Scott made chicken soup and brewed the herbs in the stock. I camped on his couch and sipped on soup and nursed away an addiction.

My cousin understands that my soup is more voodoo than nourishment. By my own standards, my chicken soup is “not so good.” She says that I get witchy when making soup and my tons of broth is more like brew.

Practitioners of Voodoo, Vodouisants, perform a ceremony one year and one day after the death of a family member or loved one. The ceremony is named retire mo nan dlo—take the dead out of the water. The spirit of the loved one is rescued and held in an earthen pot called a Govi. Vodouisants believe that through celebration, music, dance, sacrifice, and ritual the spirit world can cross into ours and help us. Through the Govi, the dead are given voice.

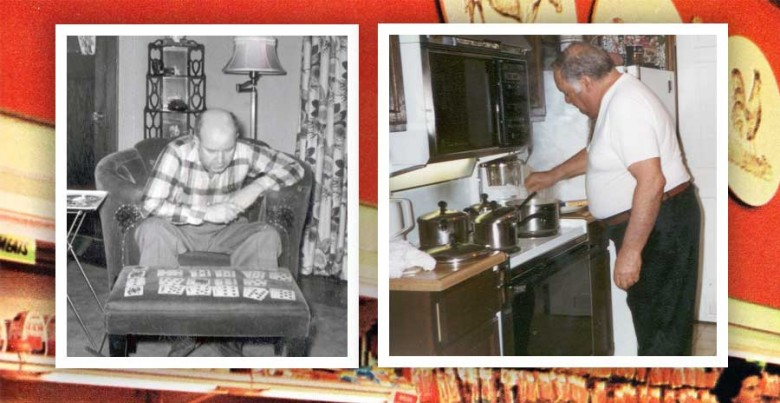

I am no Vodouisant and, for the most part death, eludes me. I’ve been to funerals, but they seemed too much like theater, almost comical in their ghoulishness—the corpse face painted with heavy make-up and everyone else dressed in black and emoting. I’ve lived in many different places and often don’t see people again. I have never attached not seeing someone to death. When my grandfather died, I finally got it. I ran up the stairs into my grandparents’ kitchen in anticipation of telling my grandfather about his own funeral—how his children read poems and psalms, how my uncles let me sip shots of Irish whiskey from their flask, how we wrote his eulogy as a family, how my mother insisted they play Ave Maria as we left the church. He wasn’t there to tell—not watching The Price is Right on the kitchen table TV, not in his chair playing solitaire on the ottoman, not sipping his soup at the dining room table. I wandered through each vacant room.

Now, I make my soup and remember. The apartment steams and the windows become opaque. The vapors of chicken soup waft like the musty scent of old age and the very air acts as a hypnotic. I begin to hear his voice, “Lesa, funny Lesa,” and I see him dressed in his golf pants and his white ribbed tank underwear, his yellow cardigan, his athletic socks and brown leather wingtips. I grate Asiago cheese over the broth and the smell of his kitchen envelopes my senses. And for that time, my soup pot is my Govi.

My diluted soup lasts. If it were condensed, I would have less of it. When it is done and I’ve sated myself, the empty and washed stockpot goes back into the cupboard. I return to my local eateries and the pickings at the restaurant where I work. I leave my family all over again. I don’t think I will ever get over that missing place, that place that is as desolate as my grandparents’ house on the day of my grandfather’s funeral, that place where I sometimes dwell in my apartment.

My brother calls me to ask how my soup fared after all the advice I was given. He doesn’t understand that the phone calls have little to do with how the soup tastes. If I made a flavorful pot of soup, there would be no phone calls, no voices in the supermarket, no reason to chronicle my family’s chicken soup stories. Sometimes my family seems so far away, they need to shout and scold for me to hear them. And if I didn’t hear them, all I would have is soup. Scott interrupts my culinary misadventures to tell me of his latest endeavor—baking. He has been making biscuits and breads and pies. My hunger blooms.

I picture us--Nana and Papa, Gram, Scott, my uncles and cousins, Dad, Mom, and me, in our separate kitchens, split-screen, like in a movie. The edge of the frame keeps us all in, but I know that soon someone will be sliced out. None of us knows what will happen or how long the movie lasts, but then I remember what Papa once said. “Finish making your soup, there’s nothing else you can do.”

This essay was originally published in Voice from the Herd: An Anthology for Buffalo, NY - a not-for-profit anthology about the present day city of Buffalo. It is a compilation of flash fiction and nonfiction, as well as poetry, edited by Alycia Ripley, Cindy Manta and Tom Waters. Topics include modern day Buffalo life, Buffalo landmarks, and Buffalonians in general. All royalties will go towards the betterment and continued success of the Just Buffalo Literary Center.