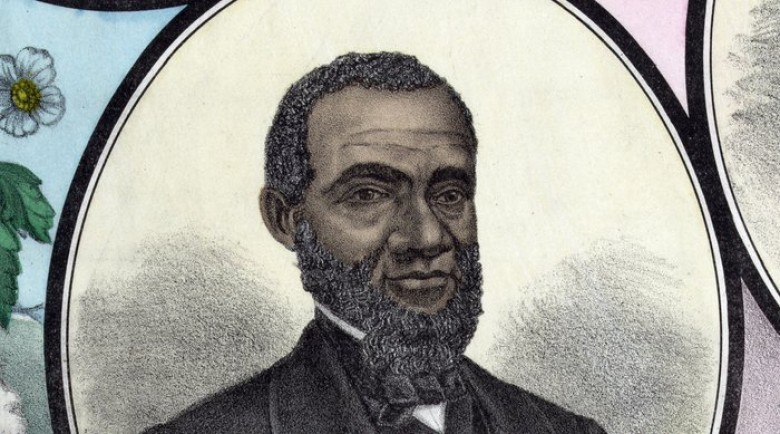

The Reverend Dr. Henry Highland Garnet. Time Magazine calls him the "the most famous African American you never learned about during Black History Month." It's about time to address this slight, especially in Buffalo.

Henry Highland Garnet was born a slave in Maryland in 1815. He escaped with his parents in a covered wagon when he was 9 years old. The family ended up in New York City, where Garnet attended the African Free School, and the Phoenix High School for Colored Youth. His classmates included Charles L. Reason, George T. Downing, and Ira Aldridge. Foreshadowing his life's work, he defended the integrated Noyes Academy in New Hampshire where he was a student with a double-barreled shot-gun and home-made bullets when it was attacked in 1935 by white farmers.

Garnet would become one of the foremost anti-slavery organizers in the world. He founded the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which waged international campaigns against human trafficking. Cuban patriot José Martí called him America’s “Moses.”

The National Negro Convention was held in Buffalo in 1843. In attendance were as many as 70 delegates from a dozen states, among them rising leaders in the African American community including Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, Charles B. Ray and Charles L. Remond. Just 27 years old, Garnet was invited to speak. His fiery address would come to be known as "The Call to Rebellion."

But Garnet's speech was not just an angry rant. He was well educated and had traveled widely. He spoke knowledgably about slavery policies in both the colonial and Revolutionary War eras, and described in detail the global state of abolitionism. He called slavery anti-Christian, and resistance to slavery pro-Christian; he said that manhood and honor dictated that (male) slaves use “every means” necessary to liberate themselves. “If you would be free in this generation, here is your only hope. However much you and all of us may desire it, there is not much hope of redemption without the shedding of blood. If you must bleed, let it all come at once—rather die freemen, than live to be slaves.” He probably sounded a lot like the Malcolm X of his day. When the National Negro Convention ended, Garnet led a State Convention of Negroes in Rochester.

Fast forward to 1926, when Negro History Week was started by historian Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. It was celebrated during the second week of February to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass and was intended to encourage the nation's public schools to teach the history of American Blacks, not just for one week, but all year long.

The 1920s was known as the decade of the "New Negro," a name given to the Post-War generation because of its rising racial pride and consciousness. Urbanization and industrialization had brought more than a million African Americans from the rural South into the big cities of the North. However, it took a half a century for "Negro History Week" to finally morph into Black History Month.

Black United Students at Kent State University proposed expanding Black History Week to Black History Month in February 1969, but this did not became official until 1976, as part of the U.S. Bicentennial. The celebration spread to the UK in 1987, and didn't reach Canada until 1995.

Black History Month is not just a time for African-Americans to celebrate their powerful history, it's actually an important reminder for all of us to learn and understand and celebrate that history. This is more important than ever in this era of Black Lives Matter and taking a knee.

One fascinating way to do this in Buffalo this month is to stop by The Albright-Knox. We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 focuses on the work of black women artists, examining the political, social, cultural, and aesthetic priorities of women of color from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s. It is intended to reorient conversations around race, feminism, political action, art production, and art history in this significant historical period through performance, film, and video art, as well as photography, painting, sculpture, and printmaking by a diverse group of artists and activists who lived and worked at the intersections of avant-garde art worlds and radical political movements. Note: Admission to this special exhibition is Pay What You Wish on Friday, March 2, during M&T First Friday @ The Gallery!

Or just get online. The Buffalo & Erie County Public Library has an remarkably comprehensive African-American Heritage Subject Guide, and also offers you access to all known legal materials on slavery in the United States and the English-speaking world in its Featured Database Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture & Law.

There is just so much much to learn. How will you celebrate Black History Month?