My nana (father's mother) wrote me a series of letters over the course of a year, one for every month in which she told me about her life in Buffalo. My favorite portions of these letters were of her childhood and the neighborhood where she grew up during the 1920s through the '30s, in the days before immigrant families had indoor refrigerators, bathrooms, and tubs in their homes. The families used the showers across the street in the park - boys on one side, girls on the other.

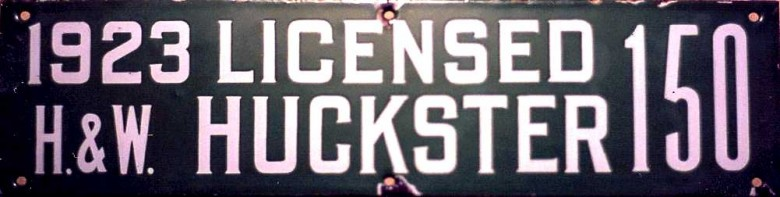

Shopping and baking happened communally, with traveling hucksters and icemen; family grocers and Italian bakeries where families could bake their bread in commercial ovens.

Nana’s June Letter

"When the weather warmed, we put a big cardboard sign in our front window. One corner had the number 25 written on it, the next corner a 50, the next a 75, and the last corner had a 100. We would turn the sign around so the iceman knew how many pounds of ice we needed for that day. He wore black leather apron to protect him. He would pick up a large block of ice and swing it over his shoulder. The drip pan under the icebox had to be changed twice a day. This worked better than our winter window box, where everything froze.

On Wednesday and Friday we could hear the fish man with his wagon full of ice and fish yelling, "fish today!" That man stank. Hucksters shouted, "cheap bananas" or "cheap string beans" or whatever else they had for sale.

We had no large supermarkets in those days, just small grocery stores. We had a little book in which the grocery man kept a record of what we purchased and once a week, when my father got paid, we'd give him a little toward what we owed. It seems like everyone had a book. I wonder if the grocer ever got paid in full. Those were the days when my mother would send me to the store for fifteen cents worth of beef and a big bone.

When it was very hot out, my mother baked bread twice a week. After the dough raised for the second time, we shaped into loaves and laid the bread on a wagon. My mother covered the loaves with embroidered linen with handcrafted cutwork, then we pulled the wagon the four blocks to the Italian bakery. We waited our turn to put them into the ovens there. On our way home from the bakery, I proudly walked home next to my mother. She was as straight as an arrow and beautiful.

When school let out during the third week of June, my mother taught me how to do cut work on sheets. I embroidered dishtowels for two hours every morning. I never mastered it like she did, but years later I became a close second. I sold the dishtowels for 12 for a dollar to the ladies who were putting together their daughters' hope chests.

If we had an extra dime on Friday, my father sent my brother down to the corner saloon to get a pitcher of beer to go with our fish. By the time he got home, the beer was flat, but boy, did it taste good."