“You can’t undo what’s done”

You wouldn’t be wrong to assume a lot of what’s happening during the course of A Most Wanted Man are red herrings steering us away from the truth it’s suspense thriller hides, but you would be mistaken. What I love aboutJohn le Carré—admittedly removed from his text in my only being familiar with cinematic adaptations of his work like the underrated The Constant Gardener and the taut Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy—is that there never seems to be any superfluity. Instead he finds a way to make his details innocuous, burrowing inside your brain until the payoff allows them to be seen as integral machinations. Every character is important, each relationship carefully constructed, and for every sideways glance or telling smirk is a demarcation for something we just can’t quite fully decipher yet.

While a lot of credit goes to le Carré and screenwriter Andrew Bovell, one can’t deny director Anton Corbijn his due for bringing everything together. The author’s work has been graced with great talent from Tomas Alfredson to Fernando Meirelles, two auteurs that chose the quiet route to keep us engaged and on our toes. I expected more of the same from Corbijn after his very cerebral and slow The American and yet he went a different direction—at least concerning sound design. I’m hoping it was a conscious effort on his part and not limitations of the theater where I screened the film, but many scenes taking place outside possess environmental sounds that almost drown out the dialogue. A perfect tool to tint everything with the voyeuristic light of espionage, it also ensures we’re paying close attention.

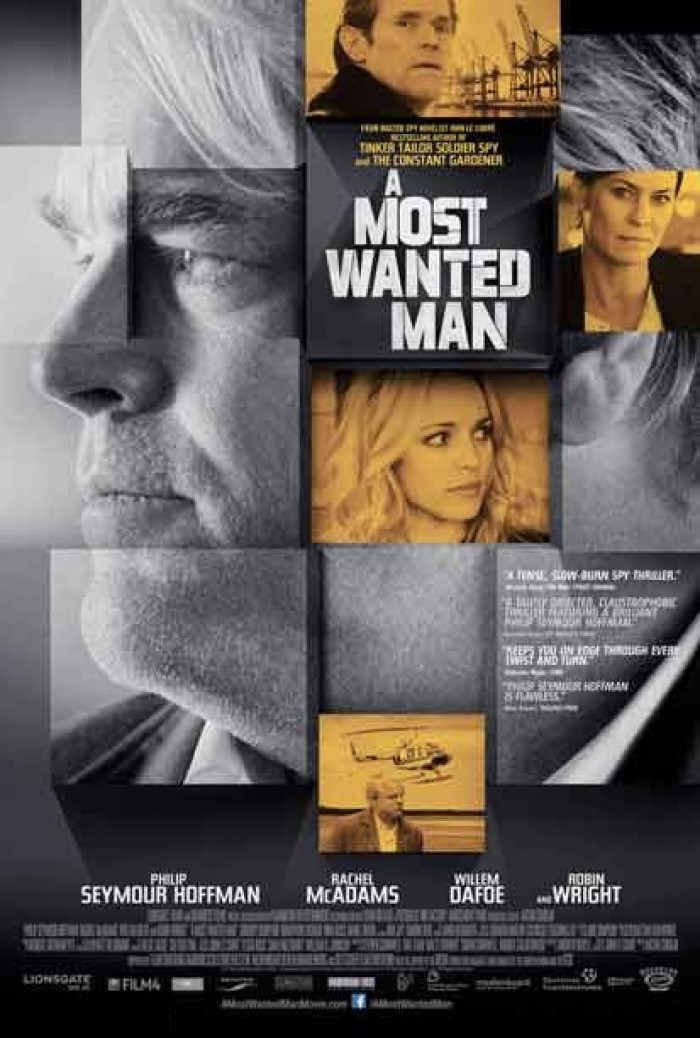

This is a requisite when experiencing his stories on the big screen. There is a lot of information thrown your way in a short period of time and you must be alert since none of it is wasted. Based on one of le Carré’s more recent novels from 2008, A Most Wanted Man looks to comment on a post-9/11 world from an international perspective. The US obviously isn’t shown in the greatest light as a result of our penchant for taking prisoners first and caring about whether they’re guilty or not second (if at all), but that viewpoint is necessary in explain the motivations of the characters we meet. And no one knows what it’s like to work opposite American ruthlessness more than clandestine German operative Günther Bachmann (Philip Seymour Hoffman), relegated to Hamburg after being burnt once before.

He takes his job seriously, though, and that hiccup did nothing for his tenaciousness besides cultivate a lack of trust for his “friends” across the Atlantic—whether someone like Martha Sullivan (Robin Wright) trying to assist him or not. What Bachmann does is intriguing in and of itself, working for a secret agency the German government can’t even recognize due to its need to exist outside the country’s own laws. He must use friends in high places to keep the authorities like Herr Mohr (Rainer Bock) back until exhausting all avenues at his disposal. Günther knows the system; he knows he must gain the confidence of those at lower levels to work up. Once you arrest your mark it will rip a hole in the criminal organization that only ends up getting refilled by someone more careful and anonymous.

The mark in this case is Dr. Abdullah (Homayoun Ershadi), a religious man lecturing on Allah’s love and the sanctity of life. For reasons gradually revealed, Bachmann believes he’s somehow siphoning clean money into the hands of those buying bombs. Without any proof he’s about out of time to discover answers as Mohr breaths down his neck to remove Abdullah from the equation altogether. And if that’s not enough, the man who could provide Günther an “in” to get close—a Chechen alien seeking asylum (Grigoriy Dobrygin‘s Issa Karpov)—is assumed a terrorist and about to be scooped up himself. So his only course of finding answers is to run interference on the German government, gain the trust of those surrounding Issa, and eventually tie them all to Abdullah before finally uncovering the person pulling the strings.

There are a lot of moving parts with Karpov’s pro bono lawyer (Rachel McAdams‘ Annabel Richter) and the banker holding his late, murderous father’s savings (Willem Dafoe‘s Tommy Brue) coming into play. Their introductions become a brilliant dance of meticulous set-ups wherein we see Bachmann or one of his numerous associates forever in the background. Corbijn places them where we can’t help but notice as they follow their marks, exit the scene, or simply exist in the background with ears open. Paranoia is bred as a result, making us wonder how easy it is to be shadowed ourselves. I’ll admit to having the urge to look behind me inside the theater to see if I was being watched. Thankfully for Issa those doing it are the “good” guys trying to use him, not those who want him disappeared.

Like any great spy thriller, those who seem in control often aren’t and A Most Wanted Man‘s best trait is its unabashed ability to show confident people pressed into desperate corners. It happens to all as each underestimates his/her situation or gets in too deep before Hoffman’s Günther can magically earn their trust. He’s a master manipulator because he’s relatable and a man of his word. But just as Hoffman was unparalleled at the everyman sympathy to achieve such, he was also a powerhouse capable of instilling fear. His Bachmann is therefore a complicated man with true moral compass who uses the carrot and stick. It’s a complex role in a complex movie ending on a note of perfection I’m glad the filmmakers bravely used, proving an appropriate swan song for Hoffman and remembrance of what we’ve lost.

Score: 9/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 122 minutes | Release Date: July 25th, 2014 (USA)

Studio: Roadside Attractions

Director(s): Anton Corbijn

Writer(s): Andrew Bovell / John le Carré (novel)