“The truth is always interesting”

It’s true what the film’s Times‘ theater critic (Lindsay Duncan) says: an artist should bleed for his craft. Physically, spiritually, metaphorically—blood must be spilt so the world knows he was here, selflessly (selfishly?) making us laugh, cry, and reflect on lives well lived and squandered. This is why those who touch upon life’s intrinsic emotions and universal feelings can demand salaries and compensation so large not even their over-stretched, ambitious, and insane imaginations can think of how to spend it all. They create what we wish we could not because we want them to, but because we need that glimpse of perfection even if only for two hours at ten bucks a head. They do it because they can and because we demand it. It’s a gift, curse, profound discovery, and meaningless triviality all at once.

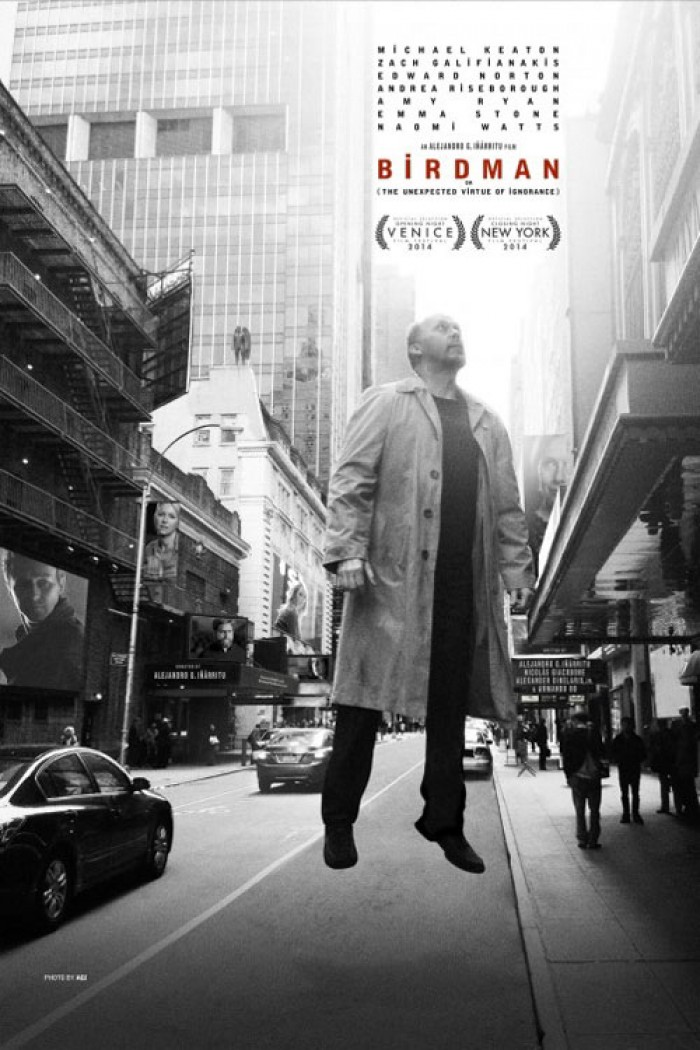

It’s also therefore a symbiotic relationship between artist and audience with one or both willfully in the dark about art’s truth. This is why Alejandro González Iñárritu‘s latest Birdman has such a fitting alternate title:The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance. That last word is key to understanding life as we know it; mankind’s desire to blissfully carry on through personal pleasure and satisfaction whether those feelings are real or made up. Taste isn’t some grand objective thing—it’s small, random, and above all powerful enough to manufacture Gods among men in those critics telling us which artists are necessary and which aren’t. Our ignorance allows us to blindly follow their lead, artists’ ignorance allows them to control their life’s works’ success and failure, and the critics simply peer down upon them all with a smile.

This is the machine we’ve signed up for. It’s what we deemed necessary as a structured backbone beneath something none of us can truly define. Art is unquantifiable—priceless to some and worthless to others. It’s a commodity we don’t need to survive, but one we must cherish in order to live. No one—not even reality TV’s biggest fans—would label the medium high art, but it’s art nonetheless if only because it touches the masses on a level that transcends time, space, and class. It hits them beyond intelligence, responsibility, or moral decency to entertain and brighten a handful of minutes spent away from the numbing assembly lined existence so many of us live. This is why we simultaneously idolize celebrities and crucify them for having what they “don’t deserve”. We love and hate them because they’re not us.

What then does this world they’ve fallen into do to them? It makes them crazy, that’s what. Whether feeding an insanity already present or gradually chipping away at their resolve until all that’s left is a raw nerve, success is a destroyer—at least until its fickleness finds it in its best interest to applaud once more before re-opening the wound at your throat. This is the chaotic, discordant journey Riggan Thompson (Michael Keaton) takes, one tackled in the hopes that it will bring redemption to a life wasted amidst the fleeting celebrity he once had and covets again. It’s been twenty years since he was more than a joke and he’s finally found a way to win back acclaim. He’ll be broke, friendless, and beaten to a pulp, but the possibility of soaring is worth the trouble.

So he sinks his finances into a Raymond Carver adaptation, hires his girlfriend (Andrea Riseborough‘s Laura) to act alongside him, the unhinged megalomaniac star boyfriend (Edward Norton‘s Mike) of his Broadway virgin lead actress (Naomi Watts‘ Lesley) to lend credibility, and brings on his troubled daughter (Emma Stone‘s Sam) as his assistant in a lazy attempt to be there for her in a time of need by paying her to be there for him. It’s a hubristic gamble that fails on paper as it does in reality once egos collide and fate intervenes. The voice of Riggan’s darker, angry self inside his head who’s ready to scorch the earth so that he may rise as a hero from the ashes he created is but merely a hiccup in comparison to the unplanned sabotage happening all around him.

The world’s about instant gratification yet he seeks to give it the type of art it and he had forsaken long ago. And somehow through the psychological turmoil that blurs the line between play and reality, tragedy becomes publicity and desperation a virtue to go along with the prevalence of ignorance towards anything but hasty dreams of being loved by anyone willing to provide it. Parallels between Carver’s work and Riggan’s life start to overlap, his descent into a broke mind caught on the ropes allows him to find the passion he locked away under the titular Birdman costume years ago on the studio lot. The Broadway stage was always meant to help expose his talent unencumbered by preconceptions and his tabloid past, but only when it falls apart can he see Riggan is as much mask as the beak.

Iñárritu and his co-writers (Nicolás Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris, and Armando Bo) don’t express this cathartic breakthrough via an overblown, pretentious therapy session of blatant psychiatric introspection. No, they instead turn it into a self-reflexive thrill ride that puts the pedal to the floor and never lets up. Besides a couple transitions fading to white or black to denote a change in time, the whole movie is presented as though one continuous take similar to Joe Wright‘s Anna Karenina‘s theatricality and Alfonso Cuarón‘s Children of Men. We don’t get a reprieve from the damaged souls onscreen because they don’t get one from themselves. And while Sam, Mike, Lesley, and Ralph find strength—with Zach Galifianakis‘ producer Jake learning to relish the deceit and opportunism of tragedy—Riggan falls deeper into psychosis until needing to merge identities through force.

Keaton’s performance is unforgettable as he goes full throttle into every facet of Riggan’s life as though it’s his as well. And frankly it is due to this tug of war being the struggle every artist must face—finding a way to exist for you despite your livelihood and career revolves around existing for everyone else. He is nonstop energy turning from lost dreamer to enraged toddler to manipulative puppet master pulling every string but his own. His Riggan yearns for what Norton’s Mike has while Mike in turn desires the innocence of youth Stone’s Sam bypassed with rebellion while she performed her own bit of acting for attention. Art merges with life in a way that lambasts celebrity and also honors humanity’s precious, fragile psyches. In the age of social media, we’re all onscreen.

In the end no one’s a hero—they’re simply men and women wading through pain and sorrow for those few morsels of happiness some never find. Much of what happens does so under the sheen of fantasy and honestly that’s appropriate considering it’s we who the camera stands in for, voyeurs watching as others watch us. No one has any answers and we’re all proven wrong. The public has an appetite for carnage and we embrace the challenge to supply it whenever possible. It’s no longer about how good you are that warrants headlines; it’s instead those human foibles setting you apart from perfection to show how the creature on the pedestal is just as human as the rest. The artist suffers for validation and the critic yearns to take it away, but the truth is that we’re all one in the same.

Score: 10/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 119 minutes | Release Date: October 17th, 2014 (USA)

Studio: Fox Searchlight Pictures

Director(s): Alejandro González Iñárritu

Writer(s): Alejandro González Iñárritu, Nicolás Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris & Armando Bo