“Life don’t give you bumpers”

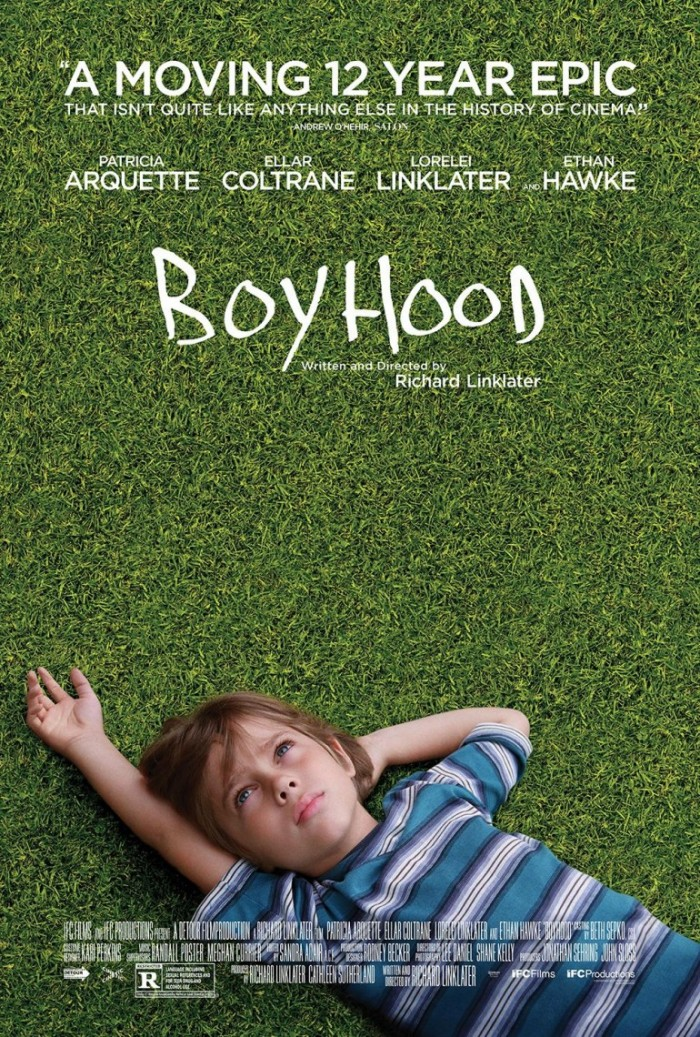

It’s almost impossible not to consider Richard Linklater‘s Boyhood one of the year’s best films on the surface. I don’t think any version of reality has the Academy neglecting to vote it onto the Oscar ballot because it’s a cinematic feat unlike few others. To fathom the number of moving parts a twelve-year shoot entails with two non-actor leads—one the director’s daughter no less—is mind blowing. To witness the result’s success critically and commercially is seeing a cherry on top for an artwork that matured from a crazy idea into a bona fide hit. But even if all that’s intrinsic to the project itself, film is nothing if not a subjective medium. So while the consensus points towards its accomplishment, the question remains whether it stirs emotions and lives up to its “masterpiece” label.

I believe it does, but saying so isn’t without a grain of salt. In all honesty the finished piece may bite off more than it can chew trying to touch upon so many universal moments in the life of a child’s adolescence that it can be a bit manipulative or in some cases incomplete. It’s never boring, though, and that’s saying something considering a close to three-hour runtime of poignant vignettes in the life of Mason Jr. (Ellar Coltrane). He and sister Sam (Lorelei Linklater) may not always be the most interesting subjects onscreen—I’d love to watch a companion film entitled Parenthood depicting the arduous, volatile, and often surprising evolutions of Mom (Patricia Arquette) and Dad (Ethan Hawke)—but they are the driving force to watch its Aughts depiction of Americana at its most complex and beautiful.

Beyond the experiment itself, the faith that all cast and crew would remain alive and interested when the camera came around for a reunion, and IFC Film’s dedication to Linklater and the project to finance it for so long, Boyhood is very much a time capsule. Some scenes drive later conversations like a brief, in-costume Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince novel release party setting the stage for Mason asking his Dad if “real” magic exists, but contrivance aside they ultimately mark moments as dear to us as they are to the characters. The soundtrack transports us back as talk of Star Wars, Obama, and 9-11 brings our consciousness in accord with what’s onscreen as only documentaries usually can. Because beneath the fiction lies a reality we lived—one that left an indelible mark Linklater has immortalized.

In that respect I can understand why so many critics love it and say it resonated in a way few films do by showing their own lives onscreen. I personally can’t necessarily count myself as one of the circle since I’m not a child of divorce, drunken abuse, recreational drug-use, or frankly anything depicted besides the fact I once was an eight-year old boy who grew up and went to college. I’m not so sure you need to be more than a human being to relate, however, because even if the details don’t match, the experience does. The teenage angst, the primary school temper tantrums, the “hatred” of your parents being parents—we’ve all been through it. Whether the shy, quiet kid (Mason) or the extrovert all about theatrics (Sam), the events Linklater has distilled recall our own.

And while I appreciate the vantage point from Mason’s eyes due to the fact we’ve all been children but not parents, I can’t help think there may be a lack of action to truly call it a perfect film. It’s not from lack of trying—and I’m sure there’s a ton of elaboration on the cutting room floor—but the feature length format means some plot lines are forgotten or simply glossed over. Are we really to believe no one tries to help poor Randy (Andrew Villarreal) and Mindy (Jamie Howard) after what’s a hard to watch series of happenings in the house of Mom’s second ex-husband Bill (Marco Perella)? Whereas Mason’s drinking and sexual awakening is perfectly introduced in subtle, intrinsic ways, the aforementioned stepsiblings are so heavily focused upon with importance and than completely forgotten.

Some things simply must get lost in the shuffle, though, and in a project this massive you must forgive it or miss the point. The court struggle and hopefully Arquette’s character’s attempts to ensure Mindy and Randy were safe might be more interesting as a specific story thread in my mind, but it’s not for a ten year old kid who cannot quite process everything happening. Boyhood is excellent at finding the balance between heightened drama and its often-insignificant effect on those surrounded by it. Yes, Mason worries about his Mom, but he also has been trained to understand she’s a survivor who prevails and moves into the next chapter of her life. As far as he’s concerned, the chaos of Bill was another stumble towards the following year’s sense of security being shaken as much or more.

These hiccups along the way shape where Mason and Sam reside in Texas, their proximity to Dad’s every other weekend adventures, and the adults they will become. He obviously gravitates towards the artsy, stoner cliques in school, but he knows the power of alcohol thanks to a string of seemingly good role models disappointing him at every turn. He slips, loses focus, and sometimes seems adrift, but there is always someone to help steer him back on course with tough love that inspires rather than frightens. And Coltrane is pure Linklater in this respect with a performance that’s always a tad more calculated than natural a la Wiley Wiggins (younger years) and full of meticulously rehearsed pontifications a la Hawke in the Before Trilogy always finding something passionate or contrarian to say when the opportunity arrives (older years).

Would the film have been effected if Mason was recast for every age group during a yearlong shoot with a revolving door of set dressing that may or may accurately portray every specific time and place? Definitely. Utilizing the same actors for over a decade is a gimmick by definition, but it’s also an inspired choice retaining a sense of verisimilitude fiction rarely does. Whereas the Up Series captured its journey in more detail by providing us multiple features, Linklater has redefined the fictional cinematic narrative in its shadow. The actors’ changing appearances, evolving climate of world politics, and surprising trends of pop culture and technology all steered this story in real time through authenticity rather than cliché and created as honest a film as can be made. It may not be perfect, but it’s damn close.

Score: 9/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 165 minutes | Release Date: July 18th, 2014 (USA)

Studio: IFC Films

Director(s): Richard Linklater

Writer(s): Richard Linklater