“I’ve always found forgiveness to be underrated”

I’m not a religious man—hell, I’m barely agnostic. I’m also not sure if that truth helps my finding John Michael McDonagh‘s Calvary as powerful as I believe it to be or simply evidence of it’s universality for both churchgoers and not. A reflection on faith, God, and ourselves caught within a present where destruction is immensely more prevalent than salvation, this story cannot help but touch you on the basest level of humanity to ask whether or not you can be better. It’s easy to hate, convenient to feel nothing, and extremely difficult to stand up for your convictions. We can’t run from our mortality or our faults and we can’t pretend nightmares that we know nothing about miles or years removed won’t affect us. We share this Earth and thusly its pain.

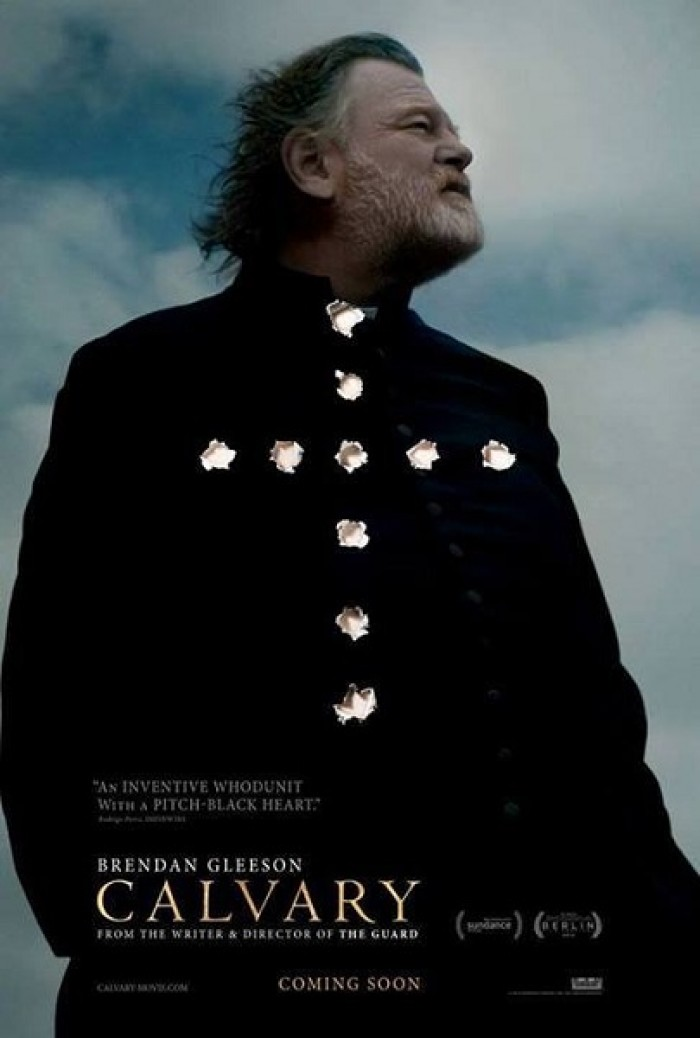

What begins under a sort of meta sheen (“startling opening line”) with an unknown parishioner confessing to Father James (Brendan Gleeson) that he was molested by a priest for five years between the age of seven and twelve—a minimalistic start focused solely on his reaction as he’s told he’ll be killed as retribution since murdering a good priest will cause bigger waves than a bad one—turns into a seven-day look at a small Irish town’s inhabitants and their jaded cynicism. Whether it everyone’s disenfranchisement with the Catholic Church or his/her own life, each faces darkness before them that they’d rather hide, ignore, or use as an opportunity for escape. And through it all stands James’ watchful eye, death staring him in the face and still unable to stop doing all he can for each one.

There’s the not-so-idyllic couple Jack (Chris O’Dowd) and Veronica (Orla O’Rourke) retaining their marriage despite his enjoying the freedom from her nagging that her affair with Simon (Isaach De Bankolé) affords. The wealthy Michael Fitzgerald (Dylan Moran) lost at a crossroads where nothing—family, money, or life—is worth caring about despite attempts to erase his numbness through a series of self-sabotaging efforts. The depressed/repressed loner Milo (Killian Scott), egotist Dr. Frank Harte (Aidan Gillen), angry bartender Brendan (Pat Shortt), praying for guilt serial killer Freddie Joyce (Domhnall Gleeson), and an on-his-last-leg elderly writer (M. Emmet Walsh) each rejoicing in their suffering and the void of nothingness looking back. Add naïve Father Leary (David Wilmot), newly widowed Teresa (Marie-Josée Croze), and James’ own daughter Fiona (Kelly Reilly) and McDonagh has certainly crafted a somber bunch.

With such quiet tumult, though, come prickly barbs of sarcasm pointed directly at James for being the optimist unafraid to call each out on their hypocrisies and bad attitudes. He’s their target, their stand-in for a deity life’s steady stream of disappointments have rendered moot. Yes, they love and respect his good nature, but they also resent the fact he sanctimoniously comes calling for business they’ve kept out of the confessional. Father James cares so much to visit and see what’s wrong that they would rather laugh at his hope than cry at their pain. We’ve all done it—most are probably in the midst of it currently—because it’s easier to deflect than face. And even though he’s the one standing with integrity, its appeal isn’t lost as the day of reckoning foreshadowed at the beginning approaches.

Gorgeously shot on location with these few characters and little else, we watch the escalation of tension as each day turns. James knows who threatened to kill him while we don’t (although it’s not hard to guess by the voice), yet he doesn’t seem frightened until the people he believed still possessed hope around him prove they don’t. Friendly banter turns cruel, the ability to talk to youths torn away in light of blanket accusations against the clergy as a whole, and personal stories hidden beneath thinly veiled jabs at the worthlessness of faith cause him to wonder what the point is too. But as he tells his daughter: he has a vocation and he will perform it because that is what’s needed. He provides assistance so the world can find its own path towards enlightenment.

There are a ton of issues packed into these 100-minutes, but none feel unfulfilled. Adultery, murderer, homosexuality, sodomy, suicide, vanity, lust, greed—you name it, Calvary has it if only to show how Father James reacts identically to all. He is nothing if not consistent in both how religion can help those “sinners” and the fact that he won’t tolerate false contrition. He’s made sacrifices and has regrets that seeing Fiona in pain can only bring to the surface at this crucial moment in his life. He makes mistakes during the course of this week too, proving he’s but a man trying his best to keep a door open and ear at attention in case someone needs it above any semblance of complete order. He isn’t naïve like Leary and he is a bit cynical himself.

It’s a brilliant performance from Gleeson—one raising the stakes of a script that sometimes falls prey to cuteness with metaphoric analogies to act structure and literary convention. To fault it for those moments would be petty, though, because there’s something to those tiny jokes specifically included for the viewer that renders us conscious of McDonagh’s aim to speak directly to the audience through his characters. He gives us a priest shaken almost to his breaking point that is honest, trustworthy, and selfless despite what others may think. So embedded with a faith and occupation that came later in life, each of James’ actions is pure to his emotions and/or intellect depending on which is in control. And with one final lesson at the barrel of a gun, he shows us the melancholy beauty of Jesus Christ’s sacrifice.

Score: 10/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 100 minutes | Release Date: April 11th, 2014 (UK)

Studio: Momentum Pictures / Fox Searchlight Pictures

Director(s): John Michael McDonagh

Writer(s): John Michael McDonagh