“Ape no kill ape”

The hype is spot-on with Dawn of the Planet of the Apes. A more focused film than Rise of the Planet of the Apes—which served as an emotive origin tale possessing little unique conflict beyond a fight scene showing off computer effects more than propelling storyline—you should still acknowledge that predecessor allows it to be so. This doesn’t mean you must view it to understand the sequel, however, as a concisely informative prologue is delivered to explain the key plot point of mankind simultaneously giving apes intellectual cognizance and humanity a disastrous virus via the hopeful Alzheimer’s drug ALZ-113. The distillation of Rise into a two-minute history lesson may actually diminish the film’s appeal, but director Matt Reeves and company don’t give us much time to notice before dropping us into the action a decade later.

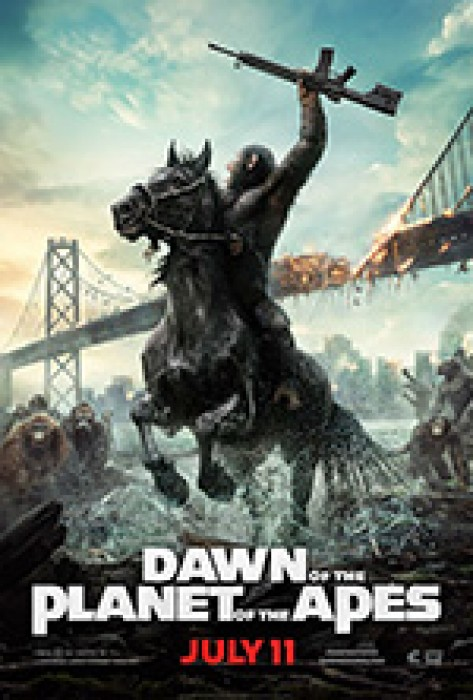

We meet Caesar (Andy Serkis) readying for a battle in the woods with son Blue Eyes (Nick Thurston) by his side and lieutenant Koba (Toby Kebbell) leading the troops. The apes have made a community, begun families, and found ways to live off the land while their human counterparts went all but extinct after those immune to the “simian flu” found depleted fuel supplies leaving them in the dark. In fact, Maurice (Karin Konoval) isn’t even sure mankind has survived at all considering they haven’t seen any in a few winters. What this means for them as a species is time for Caesar to teach his apes communication skills and the ability to achieve what we never could without internal violence and war risking everything: peace. But it all comes crashing down with a fearfully fired bullet.

Man reconnects when Carver (Kirk Acevedo) fires his gun at Blue Eyes and Ash (Larramie Doc Shaw) upon stumbling into them by a riverbed. Tempers flare as Koba—who spent his early life tortured and experimented on while Dr. Rodman (James Franco) domestically raised Caesar—calls for blood against his leader’s wish to let Malcolm’s (Jason Clarke) energy surveying party go home and never return. It’s their first spark of the rage and mistrust man has come to know all too well across the centuries from Julius Caesar and Brutus, Christ and Judas, or Cain and Abel. It’s the catalyst for fear on both sides with each quickly rallying to take up arms and move to the brink of war while only Malcolm and Caesar seek compromise via level heads and a compassion very few still hold.

Dawn is therefore a quiet tale despite its brutal pockets of violence—one about insubordination, betrayal, and the dark truth that cohabitation between apes and humans may be impossible. Dissent rises in both camps conversely as San Francisco’s leader Dreyfus (Gary Oldman) is the one fearlessly approving a fight he believes inevitable while Malcolm hopes to appeal to the apes’ want for mutually assured survival. Dreyfus and Koba say they’re willing to hold off war for now, but we know it’s all a ploy. They’ve made up their minds. So when Malcolm and Casear find themselves defenseless, we can only hope they regain the strength and voice to stop the killing. As soon as blood is shed, though, minds are officially cemented. Man and ape cannot live without fearing the moment when the other will attack.

It’s bittersweet in this way even though we know where it all leads. The film still retains the Planet of the Apes moniker its older sequels made a household name, so each glimmer of hope actually makes us sadder. We watch the beginning of human internment camps, the evolutionary leap towards ape speech, and man’s willingness to die despite knowing how few are left to make the sacrifice. The stakes are huge as they ensure future generations bear witness to kindness and malice whether it’s Malcolm’s son Alexander (Kodi Smit-McPhee) or Caesar’s Blue Eyes. They see differences put aside to heal life through the former’s mother figure Ellie (Keri Russell) assisting the latter’s Cornelia (Judy Greer) against illness. Life is also created amidst the destruction, yet more soldiers than not discover the appeal vengeance holds over forgiveness.

Because of this increased drama on behalf of Mark Bomback (who rewrote a script from Rise‘s Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver), it was crucial that the real-life actors were up to the task. The want for humor in the previous film causing so many tonal shifts has been removed and replaced by an earnest determination. The female characters are still sadly wasted (Russell and Greer) and the villainy still a tad over-the-top (Acevedo), but you do find authenticity in both Clarke and Smit-McPhee opposite the apes’ ever-evolving motion capture technology. They both expertly perform the stillness of fear, the futility of hope, and the cautious trust necessary to at least postpone the demise of an entire species. And it’s all the sort of quiet emotion Franco never received the support in Rise to give.

No matter how good they are, this is still the apes’ show. It’s amazing how life-like the first twenty or so minutes are despite what’s onscreen being mostly computer generated. Universal made a bold move letting Reeves allow a big blockbuster to be virtually silent with only subtitled sign language before Acevedo’s entrance—and it works perfectly. We become entrenched in this world, accepting these apes as personified beings on par with ourselves. It helps too that Serkis betters his already stellar performance of Caesar with insane facial detail and expressive movements. The real standout, however, is Kebbell and his fierce Koba’s psychopathy to get what he wants from ape and human alike. He’s the devil and as a result the most human of all. If that’s not a scarily poignant bit of social commentary, I’m not sure what is.

Score: 8/10

Rating: PG-13 | Runtime: 130 minutes | Release Date: July 11th, 2014 (USA)

Studio: Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation

Director(s): Matt Reeves

Writer(s): Mark Bomback and Rick Jaffa & Amanda Silver / Rick Jaffa & Amanda Silver (characters) /

Pierre Boulle (novel La Planète des Singes)