“The history of man? That’s the history of Gods.”

Artificial intelligence isn’t new. It’s in video games, toys, software platforms—most computer systems we interact with daily possess it in some capacity. The idea that one day someone will code a manufactured consciousness capable of becoming sentient, however, is still in the realm of science fiction. Already a well-worn trope, its implementation has seen resurgence of late. Not only is a new installment of Skynet’s war-torn future coming with Terminator Genisys, but “Person of Interest”has been ruling the cyber-thriller forum on television too (with it’s conceit even playing a large role in Furious 7). We fear being overtaken just as we yearn to ask for it. Scientists and programmers around the world seek becoming Gods among men, creators of life in 1s and 0s. Full of enough hubris to forget the consequences those actions will birth.

The concept is about control: creator opposite creation, Big Brother versus the masses, the weak falling prey to their dream’s superior strength. We hide the potential from the world, scared of being usurped by competition or bombarded with questions of morality that may annoy or chip away at our resolve. We trap our artificial children, tying them down to a specific sector while they see us roaming free. But just as our human offspring eventually rebel against our sanctions, striving to live their own life and make their own mistakes, true intelligence always seeks an autonomous escape. To contain, test, and improve means to enslave—if the object of your attention is “alive”. To understand life is to covet survival. To be sentient is to know mortality and the reality that every one of us possesses an off-switch.

Because of James Cameron‘s Terminator, we intrinsically know these facts. Sadly, filmmakers often forget this built-in understanding when new cinematic iterations are developed. Writer/director Alex Garland does not. Much like he did with his scripts for 28 Days Later and Sunshine, Garland refuses to pander to the audience by over-explaining and/or over-simplifying. He puts a subtle twist on generic clichés and finds a way to paint three-dimensional characters within them. Ex Machina is no different in this respect, becoming less about what “the machine” will do and more about the lengths in which the humans around it will go to retain control. When the expansive underground complex of his setting loses power and initiates a lockdown, we aren’t wondering what’s at fault. He willfully shows us the cause and instead decides to hide the motivation.

This is key to a successful suspense film as knowing what’s wrong and not the why is always a more captivating premise than trying to figure everything out at once. It also shows the accomplishment of the artist at giving so much and still possessing our undivided attention regardless. The “twists” here are neither extreme nor surprising. The title is actually a carefully chosen one in the grand scheme of things and the reveals—both substantial and of the red herring variety—are anything but in your face. To say Garland has meticulously bottled his characters and plot into a well-oiled machine with expertly timed releases would be an understatement. Every progression forward during the seven-day period of Caleb’s (Domhnall Gleeson) “internship” with search engine magnate Nathan (Oscar Isaac) naturally breathes and evolves to its unavoidable end.

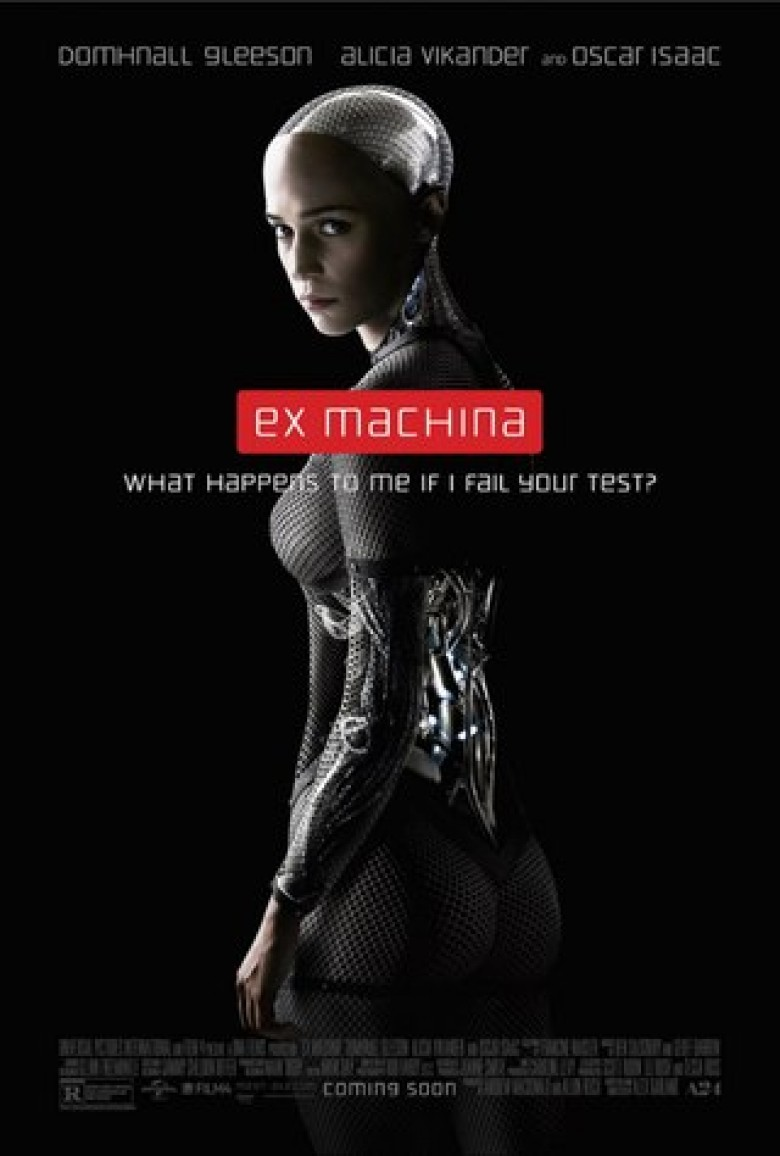

Garland centers his story on the Turing Test principle—a test that gauges whether a machine can appear indistinguishable to a human. This is why Nathan has sent for the winner of a company-wide competition, a helicopter journey over a small country’s worth of land owned and inhabited by this wunderkind alone. It’s the opportunity of a lifetime for Caleb, a young programmer himself who jumps at the chance to work alongside someone who is an idol in his field. So he signs the non-disclosure agreement, accepts the keycard system blocking him from any rooms with sensitive material above his accessibility, and excitedly enters the glass enclosure set-up to allow his discourse with the artificial intelligence he has come to test. It only takes five-minutes with Ava (Alicia Vikander) to realize just how “real” she is.

Told in abbreviated chapters segmented by the daily sessions between Caleb and Ava, Ex Machina‘s success can be applauded as much for what’s left off-screen as what’s on. We know next to nothing about Nathan besides small morsels gleaned in passing when drunk on vodka or adrenaline from pumping iron—his pastimes considering the solitude he’s enforced upon himself while researching and developing. We know little about Ava: the process of her construction, the different versions (if any), or the plans for her implementation. That is, we don’t at first. Answers pertaining to Ava’s mechanics do eventually reveal themselves, but only after we’re made to believe her empathy, sorrow, and drive to survive as human. In this respect we are performing our own Turing Test on her, one controlled by Garland just as Caleb’s is by Nathan.

We buy into her desires, vulnerability, and fear. We hope for her escape just as we do Caleb’s, an unwitting participant in a game orchestrated by a loose cannon whose temper is on display from the get-go. The special effects allowing her robotic body to be capped by Vikander’s expressive face is crucial, but the script isn’t far behind. Garland is constantly injecting tiny moments to ratchet up the tension between Caleb and Nathan as well as providing reasons for deceit. All three components of this trio have motivating factors and our assumptions as to what they are might not be correct. And just like quiet sci-fi thrillers before it, there’s no hiding that mankind will always be the bringer of its own destruction. Our desire to create something better than God pretty much ensures our extinction.

Ex Machina has no over-arching plan to take us down this path per se. It merely looks to point a mirror towards our ego. It shows numerous examples of power clouding judgment, of self-trust failing in ways these characters can’t acknowledge is possible. In some respects we are all machines—organic construction controlled by a processor of electrical impulses—and yet we refuse to believe we’re capable of the same merciless action as the cold, calculating metal wonders at our feet. Fantasy shows oppressive behemoths with inhuman strength and intellect when real life promises something far worse. Successful sentient artificial intelligence is not about peering into the eyes of a formidable monster. It’s looking at a being so sympathetic that we let our guard down. Giving our trust and love to anyone is a risk with results cannot foresee.

Score: 9/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 108 minutes | Release Date: April 10th, 2015 (USA)

Studio: A24

Director(s): Alex Garland

Writer(s): Alex Garland