“That nutty old man is my father”

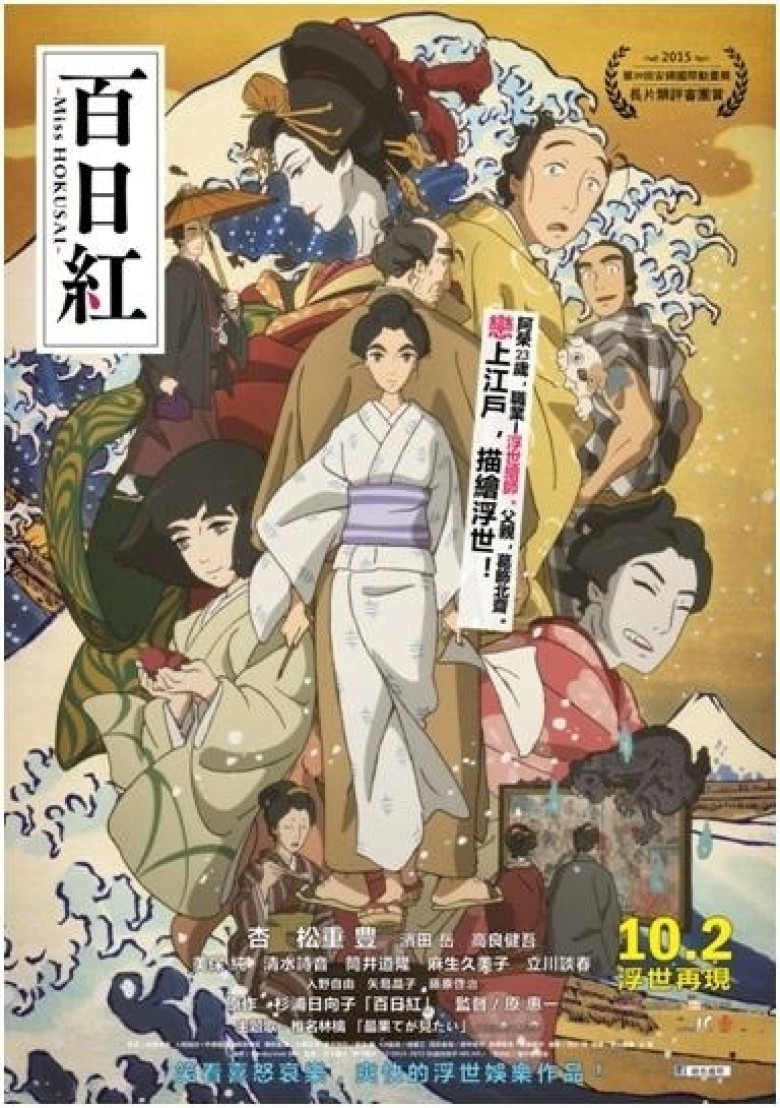

Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai‘s “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji” series is one of my favorite works of art with “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” being its unforgettable cornerstone. Even so, I never thought to myself, “Why hasn’t anyone made a movie about his life?” If you’ve seen one tortured artist biography you’ve seen them all and if the subject at hand doesn’t fit that angst-fueled mold, what’s the point? There needs to be a hook because seeing a painter paint within a cramped studio is hardly an exciting prospect. After watching Keiichi Hara‘s 百日紅 [Sarusuberi: Miss Hokusai] [Miss Hokusai]—based upon Hinako Sugiura‘s manga—however, it appears that’s all Hokusai’s story contains. The more fascinating subject proves to be his daughter O-Ei, a worthy talent living under his shadow.

This is why the title highlights her rather than her father. Unfortunately for the audience, however, O-Ei’s (Anne Watanabe) tale as presented doesn’t quite warrant a film either. All we see from her is immense skill that Hokusai (Yutaka Matsushige) attempts to bolster through tough love. He pretty much says she’s so good that she’s not good enough—wrap your head around that one. She’s so exacting that the more imperfect works of a drunk living in her father’s studio (Zenjirô as played by Gaku Hamada) are coveted over hers. Her paintings of unrest and torture cause nightmares in those who look upon them, something Hokusai must fix because he is the legend who understands the power of the brush. So they paint and we watch it dry.

Rather than craft, their family dynamic earns our main focus. This is where conflict arises courtesy of O-Ei’s younger, blind sister O-Nao (Shion Shimizu). The girl stays under the care of her aunt while their mother watches their house. O-Ei and Hokusai live in his studio because work trumps all. Do we resent Hokusai for bad parenting skills expressed mainly through indifference? Not really. The film doesn’t provide enough to conjure such a strong emotion either way. Do we think O-Ei is going too far when she constantly badmouths him behind his back? Again, no. She’s frustrated that she doesn’t earn the acclaim her male counterparts do and tired from her painting career, assisting her father, and watching after O-Nao. She’s earned the right to speak her mind.

Does it get her anywhere? No. Do we learn anything by the end of the film? No. Maybe I would appreciate this anime more if I was familiar with Hokusai and O-Ei’s work beyond “The Great Wave” as it’s inclusion as an Easter egg probably means there are a lot more of them, but even that joy of discovery and homage wouldn’t be enough to cancel the fact that the journey was so boringly hollow. The filmmakers actually introduce two prospective love interests for O-Ei to spice things up—Hokusai’s student Hatsugorô (Michitaka Tsutsui) and friendly rival Kuninao (Kengo Kôra). But their inclusion only adds more examples why she’s as dedicated as her father. She can’t be bothered by distractions. She’s devoted everything to her art without regret.

Tragedy eventually strikes to flirt with the idea of transformation or change, but everyone remains more or less the same in its aftermath. The only message I can therefore glean is that a person’s work can often outshine who they are as a person. Genius comes through sacrifice. Remove the success that we don’t see earned anyway—O-Ei is Hokusai’s daughter from a second marriage later in life—and these characters become normal people living their lives. If you bring the art back in, it still won’t add the necessary intrigue. Everything is commissioned and bought before ink hits canvas. So the only chance we have for excitement is the addition of supernatural elements. Unsurprisingly, those too prove little more than dead-ends forgotten as quickly as they’re presented.

A myth about a man’s hands leaving his body to explore the world before is recited as though memory and a courtesan at the local brothel is rumored to have her neck and head do the same thing. If there’s meaning to this in a known eastern spiritual way, however, I don’t know it. Allusions to dragons and fantastical things being seen only by talented souls is introduced too, but they’re delivered more to make Zenjirô the butt of jokes than set up some profound revelation. And if it’s all simply to make us believe the spirit of a dead person can journey after death, I can’t help but feel that I didn’t need a separate plot thread to set the stage without some purpose of its own.

What’s even sadder than the meandering story diverting our focus too often between O-Ei and Hokusai is the realization that the animation is merely good. Okay, it’s excellent as far as what it is, but it’s nothing I haven’t seen before. Nothing sets Miss Hokusai apart from other anime of a similar style. There’s no mind-blowing line work like The Tale of the Princess Kaguya or unfamiliar aesthetic to say, “Oh, that was definitely a Keiichi Hara film.” The detail is great and the environments are expansive, but I never felt a sense of awe outside of the cool use of “The Great Wave”. Again, perhaps my enjoyment would have increased if I knew more of their work to see it hidden in plain sight. Hopefully you do.

Rating: PG-13 | Runtime: 93 minutes | Release Date: May 9th, 2015 (Japan)

Studio: Tokyo Theatres K.K. / GKids

Director(s): Keiichi Hara

Writer(s): Miho Maruo / Hinako Sugiura (comic Sarusuberi)