“Pretty soon all that stands between you and being dead is you”

The question is simple: How far would you go to save your child? The dynamics, however, are more complex when the man reconciling his soul to those ends is one who’s held God’s love as a beckon of security close to his heart. Denis Villeneuve’s Prisoners opens with Keller Dover (Hugh Jackman) saying an “Our Father” as his son Ralph (Dylan Minnette) readies to kill his first deer. The words have a calming effect, one that’s helped this blue collar carpenter live the good life with his wife and children. The darkness of his past—not violent or abusive, just sadly tragic—remains beneath the surface in his psychological need to be ready, vigilant. In the end, though, he’d rather the overstocked Y2K-esque collection of essentials in his basement remain untouched.

But then the unthinkable happens. This man who prides himself on keeping his family safe is rendered helpless in the face of his daughter being kidnapped. Nothing in his basement will bring her back—everything’s worthless if there isn’t anyone to use it. This little detail, while seemingly meaningless in the grand scope of things, becomes a major driving force in Dover’s actions. It’s one of many carefully constructed expository elements screenwriter Aaron Guzikowski has included to give his mystery thriller an emotional depth that resonates beyond a run-of-the-mill procedural crime flick. Watching Keller’s wife Grace (Maria Bello) scream that he lied to her, that he failed her isn’t merely a distraught woman crazed by the loss of her daughter. No, there is truth to her words and they cut his soul.

Prisoners is therefore less about its central conceit and more about how extreme tragedy informs our actions. It isn’t a spoiler to say that the person who took his and the Birchs’ (Terrence Howard’s Franklin and Viola Davis’ Nancy) daughters eventually talks about the idea of a war against God. This is the Rosetta Stone to the whole film, the key to understanding why we’ve witnessed so much religiosity where it concerns Dover’s faith. Between the prayers, the cross around his neck, or the one dangling off his rearview mirror—God is supposed to be watching over his son on Earth. When he fails Keller by allowing Keller to fail his family, all bets are off. Evil seeps into his consciousness as he willfully partakes in cruelty with the mindset that his reasons are just.

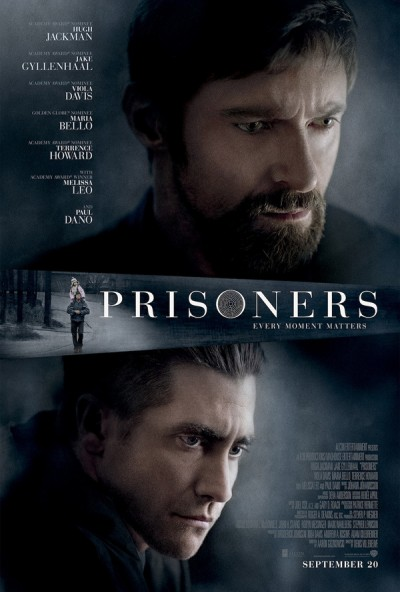

We often think the kidnapped children are the sole victims, wondering how young Anna and Joy will cope if they’re ever found alive while forgetting the impact their disappearance has on the larger scope of community and love. As Keller descends into his hellish realm built by guilt and self-hate, taking the law into his own hands by capturing the simpleminded man he believes took the girls (Paul Dano’s Alex Jones), Grace falls into an abyss of self-medication while the Birchs hover somewhere in between. Their worlds have been thrown upside-down, but they’re too blinded by rage and revenge to understand how complicated the web of horror is that surrounds them. So as Dover turns vigilante, it’s up to Detective Loki (Jake Gyllenhaal) to stay open-minded and exacting as an outsider looking in.

Like Dover and poor Alex, Guzikowski also paints his “heroic” cop in a murky light. Loki has attitude, a short temper, a problem with incompetence and authority, and tattoos from a past we hear bits and pieces from as the case intensifies. He’s a brilliant contrast to Jackman’s out-of-his-depth father—a calculating force of aggression (see his Tourette’s-like blinking tick) who somehow keeps his head when others cannot. Neither is perfect as both progress towards opposite ends of the truth. We’re privy to everything and therefore know what they do not—facts that if shared could blow the case wide open by connecting the meticulously placed dots. The tension increases as a result of us staying one-step ahead in piecing things together, desperately wanting to tell Loki and Dover what it all means.

Villeneuve ensures we spend time lingering on each one of these characters to begin to understand where they’re coming from and why they do what they do. The performances give the silence in most scenes a deafening clarity of emotional turmoil as good men and women find themselves capable of doing and/or ignoring actions they know to be wrong. The aesthetic strives to equal Fincher’s much darker and violent Se7en while mimicking the slow contemplative pace of Zodiac with false starts and unconscionable decisions making each character a ticking time bomb ready to explode. And at the center of these intelligent, cognitive souls devolving into monsters lay two broken young men (Dano and David Dastmalchian’s Bob Taylor) with minds little more mature than the girls everyone believes they’re taken.

Dover and Loki’s assumptions deflect the truth staring us in the face as their confidence steers them off-track. The former allows love to cloud his judgment while the latter risks career and reputation each passing day without answers. Howard, Davis, and even Melissa Leo as Alex’s Aunt Holly paint portraits of distressed parents, each sympathetic until they aren’t. Jackman and Gyllenhaal, on-the-other-hand, become men locked into overdrive no matter the result. They cannot afford to question their own motives or ease off the throttle while doing what the others won’t. It sends them on a collision course towards a larger horror than either could have prepared to meet, one they’ve paved with very disparate means. No longer about right and wrong or heaven and hell—sometimes surviving evil means acknowledging its existence inside us all.

Prisoners: 8/10