“They’re not trained cats. They’re just my friends.”

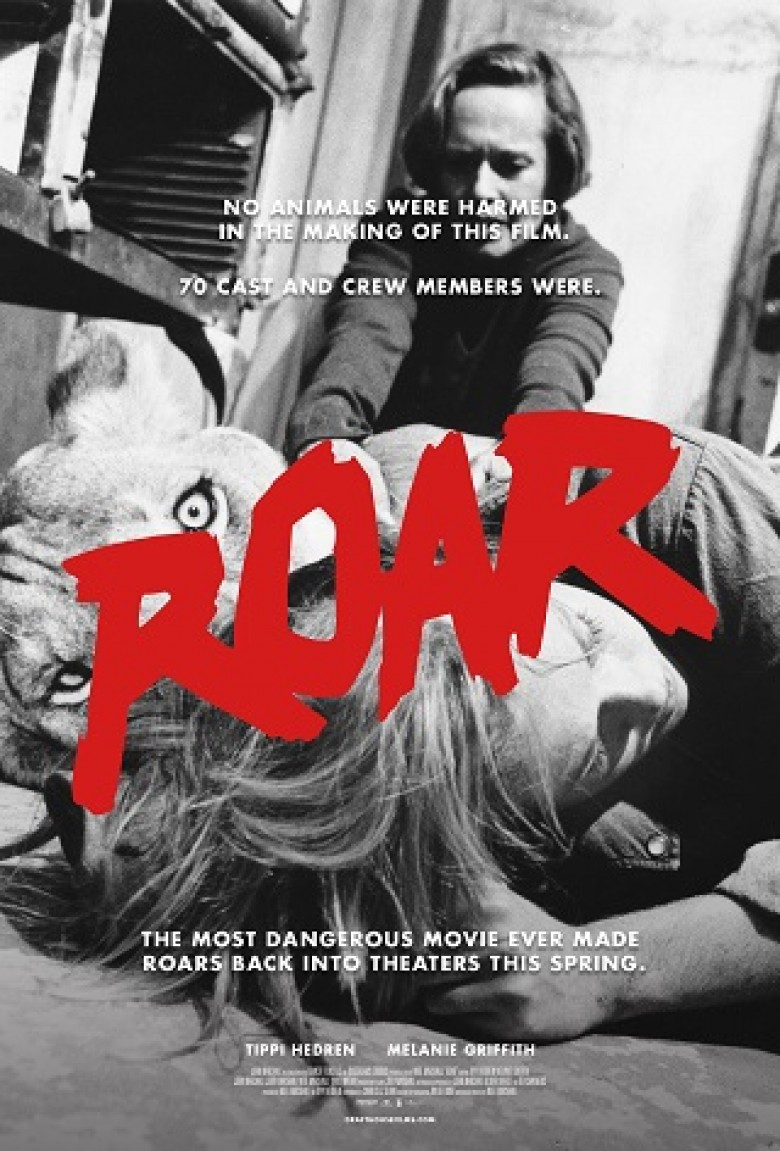

Disparaging Roar as a film means nothing in the grand scheme of things when no one will ever watch it as a movie above the near-deadly document of misguided, Hollywood liberal stupidity it is. Drafthouse Films knew this when they decided to rerelease the infamous action/adventure thirty-five years after an abysmal box office debut of two million on a seventeen million budget over eleven years of production. Their tagline, (“No animals were harmed in the making of this film. 70 cast and crew members were.”), was written to grab today’s train wreck-loving public by the jugular and plant a seed of unyielding fascination. Who wouldn’t want to watch 102-minutes of wild lions, tigers, and leopards terrorizing actors to the point of real tears and bloody gashes while their crazy writer/director Noel Marshall refused to yell cut?

I should say co-writer/co-director since Marshall relinquished sole credit to allow his furry friends a mention. Since they were untrained and uncontrollable, the executive producer of The Exorcist thought it fair to explain how crucial the animals’ actions were to shaping the story and visuals. This is because he was an insanely naïve egomaniac who truly believed he could live in harmony with these beasts despite watching wife Tippi Hedron, sons John and Jerry Marshall, and step-daughter Melanie Griffith get bitten, mauled, and tortured for years in their home and on set in South Africa. You can see it in his face and actions onscreen as patriarch Hank, baby-talking lions Robbie, Gary, and the nefariously evil Togar. Hoping to show how lovable big cats are, Marshall couldn’t comprehend that he actually made our impressions of them worse.

He may have understood—I don’t know. Hedren eventually did later on, quoted as saying how stupid they all were to have done this. But the simple fact Marshall kept going after so many years and released actual footage of his family being injured shows how deluded he was throughout the process. Griffith needed 50-stiches to close a wound that almost took her eye. Cinematographer Jan de Bont received 220 to repair an almost scalping. Noel got gangrene and was clawed by a cheetah so severely they had to halt production for years. And assistant director Doron Kauper almost lost his life when his throat was bitten open. Yet crewmembers kept gravitating to the project as others left too traumatized to continue. Somehow enough people believed Roar would save wildlife from poachers to keep going.

I thought the exact opposite after watching everything unfold. To me the heroes are two committee members attacked by tigers on Hank’s estate early that grab guns and return to kill as many cats as possible. I aligned with them because Marshall doesn’t necessarily shine them in a bad light. They literally say they will shoot these creatures because human beings are at risk otherwise. One has a sliced forehead for evidence and what happens to Madelaine (Hedren) and her kids corroborates the notion. At a certain point measures must be taken to protect those who aren’t crazy enough to approach wild animals with arms open for clawed hugs. As such, by the end of the film I honestly hoped everyone would die so Robbie and his pride could live without certifiably mad Americans playing house.

Above these asinine motivations for the horror Marshall films is the simple fact that Roar is bad. I’m talking D-movie bad thanks to Noel’s own acting. His constantly running “big” at the lions to scare them off and show strength is a safety measure and I can forgive his “coochy-cooing” dulcet tones when attempting to lull them into listening. I’m pretty certain they don’t understand a word coming out of his mouth, though. They are toying with him, batting him around because he’s a plaything for their enjoyment. The only reason no one died on-set is because the animals never went the distance. Marshall’s largest issue is the way he acts opposite the other humans, treating the terrified Kyalo Mativo like a toddler and possessing no emotional depth with his family since he obviously loves the animals more.

Hedren’s the only actor who’s actually good. Being an adult, on-board with the chaos her then-husband crafted, and a legitimate performer helped channel her real fear into the character without breaking the fourth wall. John’s as out of his element acting as his father is and Jerry seems so unfathomably comfortable with the animals that he supplies over-the-top reactions similar to those a kid would deliver in a middle school play—I think he’s faking the fright. As for Griffith, she’s so young and green that there’s a glaring separation from wooden dialogue during the calm moments and authentic screams when relinquishing all control to the lions. It doesn’t help any of them that their panic quickly disappears at the drop of a hat when reunited with Noel’s Hank. As if that crackpot could make anything seem safer.

No, the only redeeming quality Roar has is its unparalleled footage of the lions, tigers, etc. Marshall and de Bont have cameras everywhere capturing these cats tussling with each other mere feet from the actors. Watching barrels spin from the inside or entered by elephant trunks and lion claws is pretty cool. The way these animals jump on Marshall is quite a sight too. All this proves, however, is that a very successful documentary could have been made instead of the completely unhinged spectacle with amateurish plotting we received. Cemented as part of cinematic lore, the film merely shows how dangerous wildlife is and how hubristically harmful humans are. While an amazing anecdote for behind the scenes terror, it’s barely watchable otherwise. (Can someone please edit together a making of documentary? That’s what we really came to see.)

Rating: PG | Runtime: 102 minutes

Release Date: November 12th, 1981 (Australia) / April 17th, 2015 (USA)

Studio: Filmways Australasian Distributors / Drafthouse Films

Director(s): Noel Marshall

Writer(s): Noel Marshall and Friends / Ted Cassidy (additional script material)