“Who’s got the throat-slitter?”

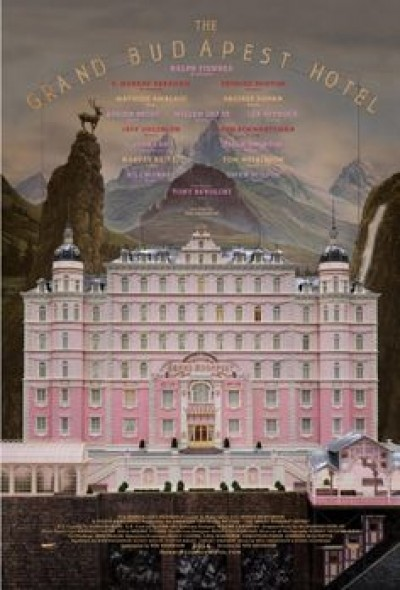

The films of Wes Anderson have always resided in some sort of parallel universe full of stylistic flights of fancy, but never has one been so completely defined by its fantasy than The Grand Budapest Hotel. His previous work exists to pay homage with stories filled to the brim by aesthetic flourishes and meticulously detailed set dressings that transport us into his familiar yet unfamiliar worlds. Rather than start with story as usual, however, his latest seems to have sprung out from its environment. This shouldn’t be a surprise considering long-time artistic collaborator Hugo Guinness shares a story credit: a man with whom you could see Anderson crafting his hotel and its elaborate surroundings in and around the fictional Republic of Zabrowka (Polish for European bison) until realizing their stable of eccentric characters needed a plot to play in.

Inspired by the works of Stefan Zweig (a popular Austrian novelist of the 1920s/30s who’s interest has waned since), the plot uses a writer much like him as our conduit into the story. Beginning with a present day girl visiting a statue to commemorate this “Author” (Tom Wilkinson), we watch her open his book about the hotel before transporting back in time to see him reading from it after its completion and further to witness his younger self (Jude Law) learning the details of Zero Moustafa’s (F. Murray Abraham) transformation from immigrant lobby boy to unobtrusive owner. In this way the movie is most like The Royal Tenenbaums, able to seamlessly travel through the decades to show an outlandish adventure of hyper-real men and women getting themselves into trouble with rare success in finding a way out.

If I had a criticism, however, it would be that this flashback construct is less a way to make the story richer than it is to disguise its lack of true dramatic weight. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed the starts and stops and quaintness of its triple-tiered framing device convoluting the frivolous dangers of Grand Budapest’s revered concierge M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes) and his young protégé Zero (Tony Revolori) while impending war by the Zig Zag (fictitious stand-in for Nazis) threatens the country in which they live. It adds up to one of Anderson’s funniest films to-date, a cinematic buffet of quirkily colorful folk played by celebrity friends who are as comically genius in expressive movements as they are in dry line deliveries. I simply wonder if it’s also his most hollow once you look beyond its surface appeal.

That may seem a bit unorthodox to say for some considering Anderson’s biggest knock over the years has concerned style over substance, but I’ve never been in agreement. His films are obviously not for everyone and always a bit left of center, but I’ve never necessarily found a false note (at least where they concern their place in their respective world). Within these tales of familial strife and/or innocence lost along the journey of life, every character finds an evolution we can relate to (more so if you’re a white suburbanite with middle class or higher background, I will acknowledge that). With The Grand Budapest Hotel, however, I found myself at my most distant, watching from afar at the antics onscreen as though it was more a farcical comedy of errors than anything truly resonate.

Does that mean it deserves a low score? Definitely not. While it may not be on par with the auteur’s best, it’s still a solid piece of escapism that keeps you riveted to discover what happens next. We know Zero obviously inherits the priceless painting M. Gustave received himself courtesy of a love affair with the late Madame D. (Tilda Swinton), but we haven’t a clue to how because the constant insanity is too far-fetched and off-the-wall for guessing. With a surprise relationship between Gustave and army officer Henckels (Edward Norton); Madame D.’s son’s (Adrien Brody‘s Dmitri) slack-jawed muscle Jopling (Willem Dafoe) forever in the background wreaking havoc; or a fugitive butler (Mathieu Amalric‘s Serge X.), hardened criminal (Harvey Keitel‘s Ludwig) and cult of neighboring concierges (including Bill Murray and Bob Balaban), there isn’t a moment’s breath to be had.

Our focus moves from Gustave’s plight (played with impeccable delight by a Ralph Fiennes who’s never been this funny) and Zero’s (Revolori proving one more example of how either Anderson as a director or his made-up universes of awkward are perfectly suited for unknown actors), experiencing their budding friendship through a jailbreak, art theft, and violent shootout. F. Murray Abraham’s recounting of course shines Gustave in a heroic light that may or may not be accurate, but it definitely instills the love he had for the man as a father figure when he possessed nothing more than fiancé Agatha (Saoirse Ronan) and the clothes on his back. We want both to find happiness and freedom against a pursuing army and vengeful nemesis (Brody), knowing Zero lives and hoping Gustave does too at least for a little while.

It therefore seems a sprawling piece of intrigue and complexity even if not necessarily anything more than a lonely man talking of implausible adventures through Zabrowka as a boy to whoever will listen. The package containing it is vintage Anderson with more matte paintings and superimposed actors on elaborate maquettes than ever, storybook chapter titles of impeccable and relevant design, and a cast of “straight men” keeping us in stitches for its entirety just by their wide-eyed reactions and calm deliveries of expertly written barbs without the smallest artifact of smirk breaking the artifice on display. Even the multiple aspect ratios (How has it taken this long for a master of symmetry like Anderson to shoot full-frame?) help ground us in time and place so as to never be confused by its sequencing.

One could easily create five cinematic offshoots by following other characters before or after—that’s how rich this film is on paper. When the sky is the limit as well as history and geography easily malleable to suit the director’s needs, what cannot be accomplished? Do I wish I could have aligned myself more with Fiennes’ Gustave, Revolori’s Zero, or even Law’s “Author” to really feel their emotional roller coasters beyond an audience member’s glee at their unique actions in extremely distorted situations? Yes. Thankfully, though, while such a realization would have ruined the experience altogether for a work by a less skilled filmmaker, Anderson is comfortable providing dizzying storybook fairy tales for adults. I do hope his next finds a solid focus again, but I can’t say I’d mind another escapist farce either.

Score: 8/10

Rating: R | Runtime: 100 minutes | Release Date: March 7th, 2014 (USA)

Studio: Fox Searchlight Pictures

Director(s): Wes Anderson

Writer(s): Wes Anderson / Wes Anderson & Hugo Guinness (story)

Stefan Zweig (inspired by the works of)