“The little one has done it”

To me Stephen Hawking has always been synonymous with physics I will never understand and that ubiquitous computerized voice cracking snide jokes. Until I saw the trailer for James Marsh‘s The Theory of Everything I never even knew he was once able to walk. It was kind of a mind blowing revelation for an ignorant fellow such as myself—one of the greatest minds of the twentieth century bound to a wheelchair without motor function suddenly shown to have been a once vibrant young Cambridge Ph.D. student in love who would go on to father three children over the course of a still ongoing life despite his diagnosis of ALS in 1963 coming with a two-year lifespan. So unless you yourself are a theoretical physicist, it’s this human portion of Hawking’s tale that provides the intrigue.

In comes his ex-wife Jane‘s book Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen and screenwriter Anthony McCarten‘s fascination with the man behind A Brief History of Time. The science itself therefore takes a backseat in the adaptation besides a few milestones and Jane’s interpretation of Stephen’s work often spoken out of frustration. We’re instead shown the unlikely love story binding them together despite mounting tragedy and the knowledge it could end only in heartbreak. If the film’s timeline is true to life Stephen and Jane weren’t a couple for long before receiving the life-altering news. The pain of what it meant drove him to try and let her go, but she wasn’t so quick to comply. Their bond was too strong and she made certain she’d be by his side for whatever time he had left.

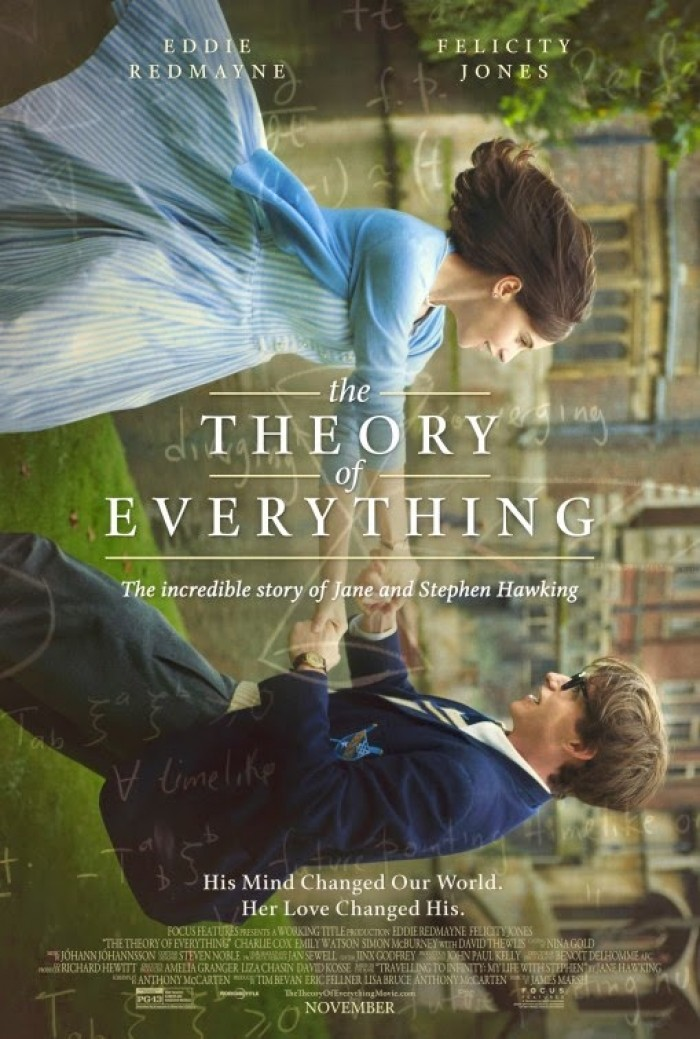

It’s a beautiful tale of perseverance against all odds: a wife doing all she could for her husband’s genius and his gradually understanding the prison he helped her to trap herself inside. For every victory with black holes and singularity Stephen (Eddie Redmayne) has came more struggles for Jane (Felicity Jones) to look past self-identity and continue to give everything for her family instead. There would be children running about, trips planned to far off places, and an ever-vigilant process to keep the man she loved alive that no one else quite knew the difficulty of but Stephen. So when help finally arrives courtesy of the church’s choir conductor Jonathan (Charlie Cox), everyone watches with skepticism and distrust despite her being the first one by his side whenever a new wrinkle presents itself.

And boy is there more than a few wrinkles throughout their marriage. From his degeneration into a wheelchair, the tracheotomy that took his voice, and the mounting pressure each new child brought, no one could think they were a normal family despite how hard they tried lying to themselves. Ultimately Stephen devoted his resources towards the science, leaving the rest for Jane to mop up behind him. Marsh and McCarten take special care to never show too much of their friction and ruin any mystique, but there’s enough to subtly express how their troubles were as real and important as our own. In some respects this film is rightfully a biography of the woman behind the man. Jane Wilde Hawking: the rock whose absence from this earth would have ensured our never knowing the Stephen Hawking of today.

As such, The Theory of Everything spans around two decades of their life together like any conventional biopic would. Patches of boredom set in as a result and more than a few moments of emotion arrive to see who’s been drawn into the drama. Thanks to Oscar-worthy performances from Redmayne and Jones and a thoughtful script devoid of tabloid sensationalism, however, it never devolves into the sordid soap opera to which a marriage on the rocks could fall prey. We infer the distance growing and the desire to escape from each—we don’t need the filmmakers to spell it out and put each sin in our faces. In the end they have three children together and a lasting friendship grounded in a love beyond any minimalizing definitions. Their fracture must therefore be gradual, authentic, and mutually reached.

Is that how it actually was? Being a narrative film it doesn’t really matter. Parts are glamorized and polished, others dumbed down so not to alienate audiences unversed in physics, and hardships condensed into a rolling thunder rather than crack of lightning. Being a love story means it must ultimately prove uplifting despite the troubles along the way and Marsh does a nice job cultivating that feeling without overstepping into pure sentimentality. Mini episodes of anger temper the idyllic landscape and we’re shown Jane’s internal wrestling as well as her unwavering devotion. With her is Stephen’s constant awareness of everything around him—his eyes and ears watching and hearing in spite of being locked in place. We know their love in the good times and bad because it never disappears from the moment they meet to the credits.

That’s not easy to pull off when you’re putting your characters through so much. It’s a credit to the actors for retaining such emotional weight when it would have been easy to replace it with resentment. This is the power of Stephen and Jane Hawking and why their story earns a feature-length film. It’s messy from the start pitting together an atheist and an Anglican, scientist and artist, who agree on just one very important thing: each other. That’s what sticks with you above Redmayne’s impressive portrayal of Hawking’s disability or Jones’ complex depiction of a woman full of strength and compassion who’s continuously underestimated. Not even Stephen himself could quantify their fateful meeting or why they needed each other so much—although I’m sure he tried. Yet here’s the worthwhile product of it just the same.

Score: 7/10

Rating: PG-13 | Runtime: 123 minutes | Release Date: November 7th, 2014 (USA)

Studio: Focus Features

Director(s): James Marsh

Writer(s): Anthony McCarten / Jane Hawking (book Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen)