My father loved sports. His favorite sport was baseball and his favorite team was the New York Yankees. He made me a convert and for my sixteenth birthday he drove me to Cleveland to watch the Yankees play. When it was time to head home, he surprised me. I got to fly home. He drove back to Buffalo on his own. That’s when it happened. On his drive home, while I was giddy, flying high on my first plane ride, my dad suffered a massive heart attack.

As a young man, Dad played baseball and football in the city leagues. As he got older and judged himself too slow, he went to night school and learned to be an umpire and referee. He bowled a few nights a week and was good enough to be invited to join the professional tour. As a family man, he turned down the invitation citing travel and the unknown financial risks. He did shiftwork at Bethlehem Steel and, in strike years, he worked two side jobs. He also liked to play poker and the horses. I didn’t see my dad much but that didn’t stop me from being a daddy’s girl.

At age fourteen, I joined a bowling league. Dad was my coach. When he was home, we played catch and he taught me how to swing a bat and field a ball. I played baseball with the boys between the islands on Harding Road, our street in South Buffalo.

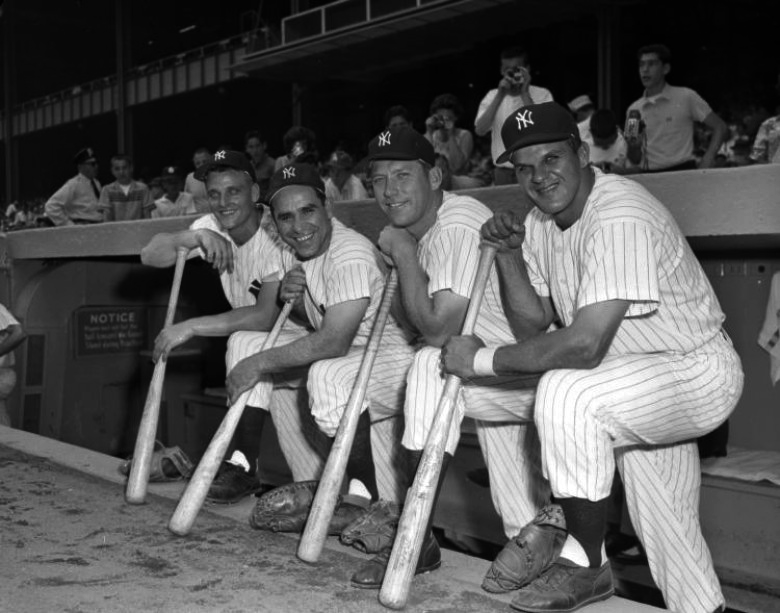

The year was 1958, the Yankee roster included Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford, Casey Stengel and Bill "The Moose" Skowron, my teenage heartthrob. In Cleveland, I watched Whitey Ford pitch a shut-out, Mickey Mantle pound a triple and we sat close enough to the first baseline for me to drool over Bill Skowron.

Then, an airplane ride home—I was nervous in the airport and getting on what looked to me like a very small plane (a commuter—it was only a forty-minute flight). But once we took off, I was sold. The thrill of picking up speed on the runway and rising into the air, to be transported so quickly to a place far, far away—the seeds of a passion for travel entered my soul and sprang roots. I loved it. What a gift!

When dad arrived in Buffalo, he entered the house and told my mom he wasn’t feeling well and needed to lie down. A few minutes later, he called out to her. Crushing chest pain shot down his left arm. Mom called an ambulance. Dad arrested in the ambulance and again in the Emergency Room.

My dad was a religious man who obeyed the rules—mass for he and his family every Sunday (until my mom said ‘enough’ and then it was just dad and the kids), confession on Saturday whether you needed it or not; Catholic school and the tuition that goes with it for his kids (not easy for a laborer); tithing—a secret he kept from my mom until the church finally got around to sending out receipts and then Hell To Pay; rosary beads under his pillow; and in later years, he was a deacon. He read scripture at mass and assisted with Holy Communion. He knew his way around the deities, had done his part, and while on death’s door, felt comfortable enough to broker a deal.

He told me later that, in the ambulance, he made a deal—if God would let him live until his young children were raised, he would be willing to die an excruciatingly painful death instead of the relatively easy one he was now experiencing. Since his heart stopped again after he proposed the arrangement, I figure God had to think it over before signing on. I also question the “easy” death idea, but he never questioned any of it.

My mother and I didn’t share my father’s great faith but I recognize how I benefited from it. It helped to make him the strong, responsible father that he was. But more importantly, it kept him alive. My mom went to the hospital every day, sat by his side, held his hand and made it clear that her faith resided in him.

Dad was forty-five years old, the father of fifteen and twelve-year-old daughters and four-year-old and nine-month-old sons. Each day, our house filled up with extended family who helped with everything. My maternal grandmother reminded us repeatedly that my father was a “good man.” He ‘took care of business’ and loved us very much. I remember this time as busy, cruel, scary but also joyful, when all of us were in synch with a common goal. The longer he was in the hospital, the more confident I got that he would get better. After six weeks, he was released from the hospital and prescribed an extended recovery period.

In our living room, his chair was one of two positioned in front of the RCA black and white television. He played solitaire on a rectangular-shaped, plastic-covered footstool. Most days, he watched sporting events, played solitaire and took naps. His doctor laid down a new set of rules and got dad on a healthy lifestyle regime. He bought a juicer (in those days, big, noisy and messy—my mother hated it) and made carrot and celery juice, he reduced his intake of fatty foods and red meat (switched over to a daily diet of chicken) and stopped smoking and drinking.

But he didn’t go bowling, to the baseball or football fields, or even to the stadium to see the Bills play. When he wasn’t making juice, he sat in his chair, watched television and played solitaire. After school and on week-ends I sat in the chair next to him. Having him so close and so inactive brought my fears to the fore again. I was afraid, first for my father and then for my own teenaged self. What if he didn’t get better? What if he had another heart attack? What if he died the next time? What if I were left alone with my irritable mother, pesky little sister and noisy little brothers? And with my father underfoot and the worry about his health, my mother was getting crankier by the minute.

“Pretty boring, huh? Just watching TV all day?” he would say.

“No, no Daddy,” I would reply, “not boring. I like watching TV. It’s nice and quiet.”

I was a teenager. I was bored. But my job, as I saw it, was to cheer him up because he seemed so sad; to quiet him if he became upset; to keep the annoyances of a busy household at bay; and to take his side when he and mom argued. I learned to watch sports with the same rapt attention as dad. We were a team and we were fighting a war. Outwardly, we fought for the Yankees and the Bills. Inside, we fought for his health and a return to normalcy for our family. If we won, dad would get better. Losing wasn’t an option.

It was the first-year anniversary of his heart attack. My favorite couple, Justine and Bob, danced a jitterbug on American Bandstand. Dad got up out of his chair, went to the front closet and pulled out his bowling bag.

“C’mon,” he said, “I can’t sit around this house for the rest of my life. We’re going to the alleys.”

My sixteen-year old heart beat wildly. He hadn’t been bowling since his heart attack. He wasn’t even back to work yet.

“Did the doctor say it was okay?”

“Ah, what does the doctor know.”

“Where’s mom?” I asked in desperation.

“She worries too much. C’mon, I said.”

We went to the bowling alley. In his first game, he broke two-hundred. The next day, he went to his doctor’s office and told him he wanted to go back to work.

He never revisited the ball fields as a player, an umpire or a referee. He continued to bowl and took up golf. Soon, he was good enough to compete in local tournaments. If he was home on Sunday, he watched the Bills on television. He listened to the Yankees on his car radio. In one way, I had my dad back. In another way, he was gone again. We never took another trip together. In fact, he was reluctant to travel at all.

In the ensuing years, Dad suffered many health crises including open heart surgery. But with his faith, determination and unwavering ability to follow the rules, he survived to the age of eighty-four. Now, when I attend my grandson’s baseball game. I feel him sitting next to me, cheering and coaching. "Atta boy, keep that mitt on the ground, eye on the ball, elbow up."

I will miss him always.